Lek M. Gjeloshi was born in Shkodër, Albania in 1987. He graduated from the Fine Arts Academy of Florence in 2010. His work has been shown in several solo and group exhibitions since 2007. In 2016 he was the winner of Ardhje Award for Young Visual Artists, organized by TICA – Tirana Institute of Contemporary Art in Albania. In 2018 he was artist-in-residence at Residency Unlimited in New York.

All My Colours Turn to Clouds

Exhibition

2016

The exhibition by Lek M. Gjeloshi starts from the idea of creating a space where the works are manifest only in light, meaning that of the projector as well as the luminous screen surfaces and illuminated volumes. It is creating monochromatic zones with a wealth of greys and where every step takes the visitor deeper into the Stimmung, or atmosphere, of a world in continuous transition even if the first impression is that almost nothing is happening. However, the seduction of the passage could easily slip into disappearance.

The title, All my Colours Turn to Clouds, is a short fragment of a song by the British Post-Punk group Echo & The Bunnymen contained in their album Heaven Up Here (1981). It proposes the vanishing of colours in a meteorological passage as an assumption.

The exhibition included – among others – two new video works:

Untitled #2 opens on a place known as Rana e hedhun (known in Italian as la sabbia gettata or strewn sand), a zone of the north-western Adriatic coastline in Albania characterized by a suddenly oblique alignment of the sand that distinguishes (and separates) it from the surrounding environment. This is also the starting point for the video with an uncut black and white sequence in which the flow is marked only by the presence of a wayfarer and the camera shot which follows the oblique plane of the dune rather than the (natural) line of the sea, completely overturning its horizon line as well.

In Unknown, the author takes us to another place, a village called Guri i zi (known in Italian as la pietra nera or the black rock), just outside of the city of Shkodër. The central part of this place is built around an outcropping of black stone, the origin of the place name. Despite the intimate connection between its volume and the habitations, its outlandish nature remains estranged in its surroundings. In fact, the word itself has retained the same meaning from archaic times and refers to something strange about a foreigner and his anonymous land. Some opinions, mostly popular credence, believe the stone is a meteorite.

The real people went away

Series of 35mm negatives

2018/19

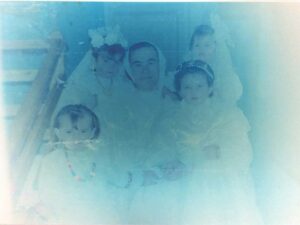

The real people went away is a series of digital images made from rolls of exposed photographic film that the artist received from a friend. Gjeloshi began by testing the film on an old machine for viewing 35mm negatives. The exposures that he discovered were veiled in mystery as they arrived without any context or information: dark nuns walking in the snow, people walking through apocalyptic, crater-filled landscapes, bodies frozen in mystical gestures… He photographed the negatives on his smartphone and used an application to overlay another negative filter, to create a hybrid, positive image saturated in cyan blue. Using this unconventional method to develop, or rather convert, the images digitally, the artist produced a charged, new atmosphere that emphasizes their ethereal and phantom-like presence.

Gjeloshi recognized that the images were taken in Shkodër, his hometown, and — without a doubt — after the 1990s, as Hoxha’s regime completely forbade the practice of religion as of 1967. Until the end of the regime, the churches in Shkodër were either destroyed or repurposed into things like a puppet theater or a sports palace. Religious observance persisted in private. In the 1990s it resumed as a communal, public practice and was supported by international aid from the Catholic Church and other missions that poured in when Albania’s borders re-opened.

Liberation in 1990 was immediately followed by political crisis and chaos. As he was a child in this transition period, Gjeloshi only later identified the confusion that came with the transition from one ideological system to another as its own kind of violence. The children captured in the images are around the same age as the artist, and so most, if not all of them, are still living. By converting the images on his phone, the artist plays with the idea of religious conversion; the resulting, hazy filter allows him to identify with the figures in the film while also manifesting his feeling of alienation from them and the time period depicted.

(Amy Zion)