Uriel Orlow lives and works between London and Lisbon. He studied at Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design London, the Slade School of Art, University College London and the University of Geneva, completing a PhD in Fine Art in 2002. His practice is research-based, process-oriented and multi-disciplinary including film, photography, drawing and sound. He is known for single screen film works, lecture performances and modular, multi-media installations that focus on specific locations and micro-histories and bring different image-regimes and narrative modes into correspondence. His work is concerned with residues of colonialism, spatial manifestations of memory, blind spots of representation and plants as political actors.

Orlow’s work has been presented in many international survey shows including Lubumbashi Biennial in 2019, Manifesta 12 in 2018, Sharjah Biennial 13 in 2017. His work has also been shown internationally in museums and galleries including Tate Modern and Whitechapel Gallery in London, Palais de Tokyo in Paris, Kunsthaus Zurich and Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva amongst others. Orlow’s films have been screened at the Oberhausen Short Film Festival; the Locarno Film Festival; Videoex, Zurich, Switzerland; Centre Pompidou, Paris; BFI, London; Kino der Kunst, Germany, and elsewhere.

Soil Affinities

Exhibition views

Pdf Introduction of Soil Affinities, Rennes/Paris: Shelter Press, 2019

2019

Soil Affinities takes its starting point in Aubervilliers’ 19th-century market gardening past which ended when factories started to take over, around the same time as European countries, including France, began to develop a colonial agriculture in Africa. Soil Affinities is guided by a series of interconnected questions: What remains today of Aubervilliers’ market gardening past apart from the town’s street names? How can plants become a compass to map historical and contemporary (post-) colonial relations?

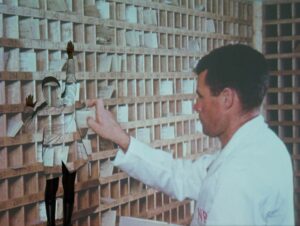

In 1899, following the infamous Berlin conference which divided Africa between the European powers, and around the same time as suburban agriculture had to make space for new industries and their factories in Aubervilliers, the French colonial department created the colonial test garden at the Eastern end of the Bois de Vincennes in Paris. In specially designed transport boxes — the so called Ward crates — plants would be shipped from the Americas to Paris and from there to the newly set up test gardens in Dakar, Saint Louis and elsewhere in West Africa. Over time those same gardens also started experimenting with and cultivating European staples — such as tomatoes, peppers, green beans, onions, cabbage etc. —for the growing French settler population. The large scale cultivation of staple vegetables in West Africa — as opposed to the previous economic plants such as cocoa, coffee, peanuts etc. — took off after independence from France in 1960 with a number of French and European companies creating industrial farms in Senegal producing almost exclusively for Rungis, one of the biggest wholesale markets in Europe, just outside Paris.

Soil Affinities traces these lines and networks of terrestrial connections between plants and people, across different geographies and temporalities, through video, photography, and other documents gathered in France and Senegal over the past year. The installation is conceived as a display of these materials, in a horizontal, non-linear manner that allows them to speak for themselves as well as cross-fertilise each other.

The Fairest Heritage

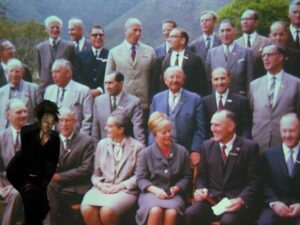

Single-channel video, 5’22”, stills

2016/17

In 1963, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the founding of Kirstenbosch, the national botanical garden of South Africa in Cape Town commissioned a series of films to document the history of the garden, the Cape Floral Kingdom, and the jubilee celebrations with their national dances, pantomimes of colonial conquests, and visits from international botanists. The films’ protagonists – the scientists and visitors etc. – are all white; the only Africans featured are labourers. Considered neutral and passive, flowers were excluded from the boycott until the late 1980s and so botanical nationalism and flower diplomacy flourished unchecked at home and internationally.

The films have not been seen since 1963 and were found by the artist in the cellar of the library of the botanical garden. Orlow collaborated with actor Lindiwe Matshikiza who puts herself and her body in these loaded pictures, inhabiting and confronting the found footage and thus contesting history and the archive itself.

Imbizo Ka Mafavuke (Mafavuke's Tribunal)

Video, trailer

2017

Imbizo Ka Mafavuke (Mafavuke’s Tribunal) is an experimental documentary set at the edge of a nature reserve in Johannesburg. A kind of Brechtian Lehrstück, the film shows the preparations for a people’s tribunal where traditional healers, activists and lawyers come together to discuss indigenous knowledge and bio-prospecting. The pharmaceutical industry has come to consider traditional medicine as a source for identification of new bioactive agents that can be used in the preparation of synthetic medicine. This raises new questions about intellectual copyright protection of indigenous knowledge.

Imbizo Ka Mafavuke asks who benefits when plants become pharmaceuticals, given multiple claims to ownership, priority, locality and appropriation. The protagonists in the film slip into different roles and make use of real-world cases involving multinational pharmaceuticals scouting in indigenous communities for the next wonder drug. Ghosts of colonial explorers, botanists and judges observe the proceedings.