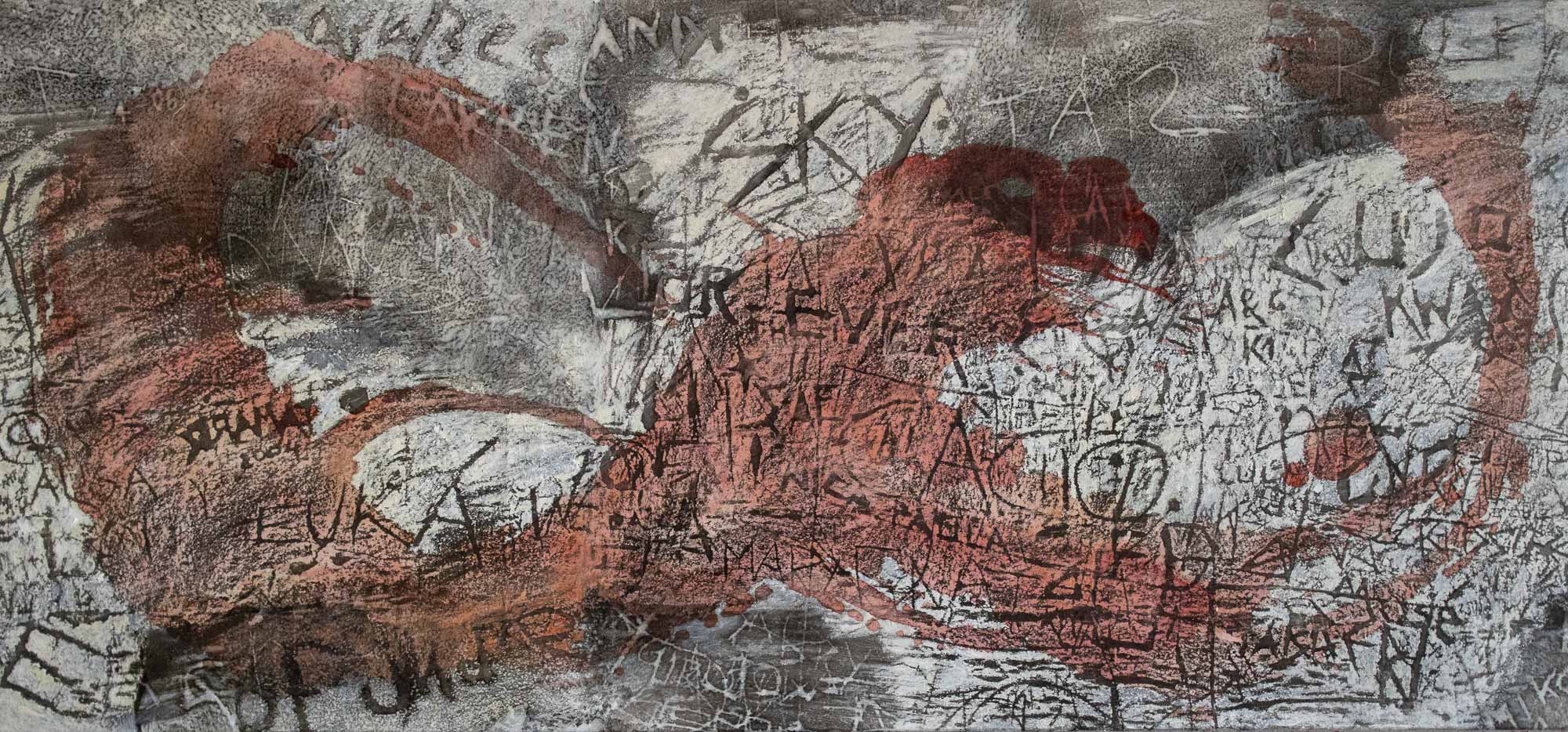

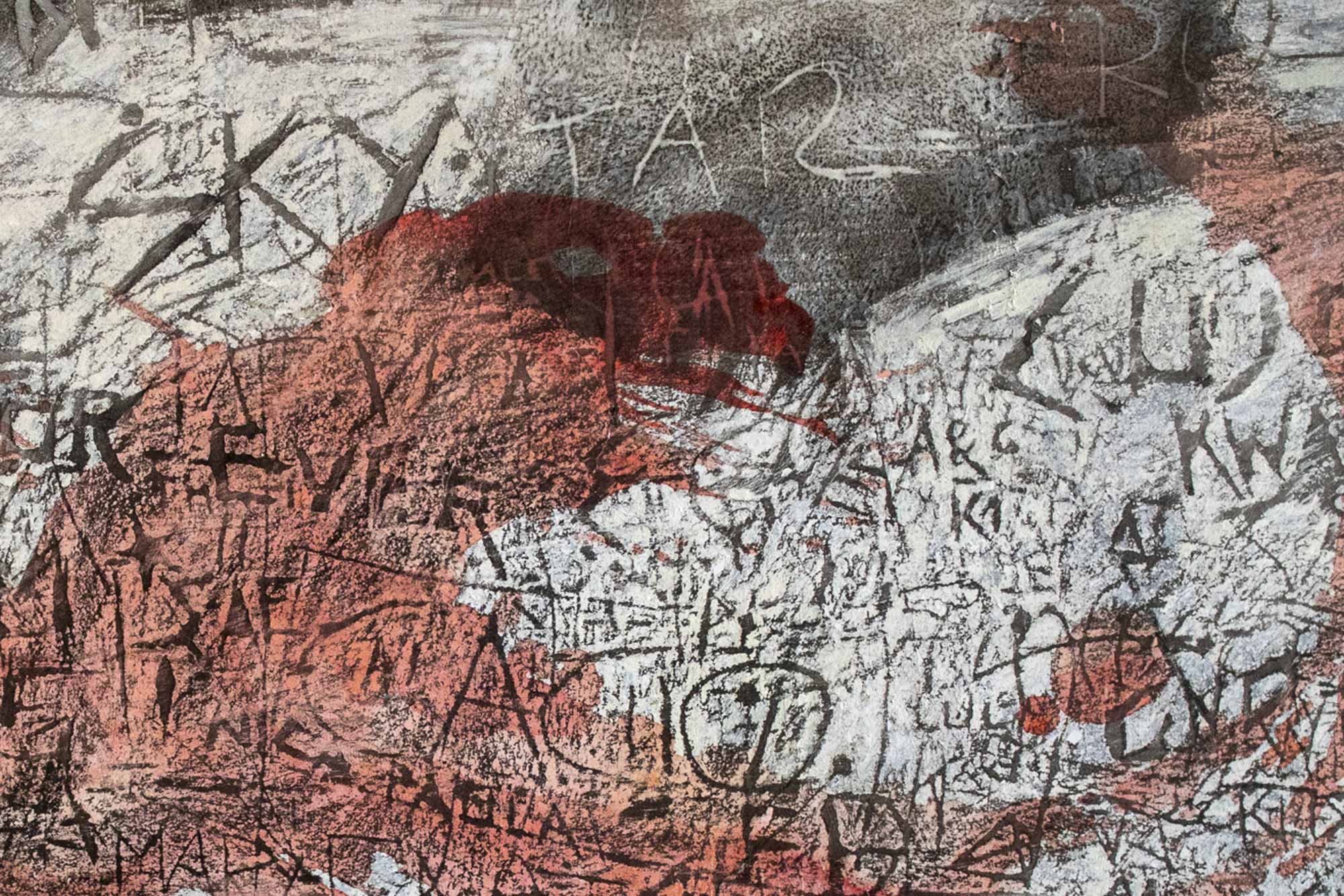

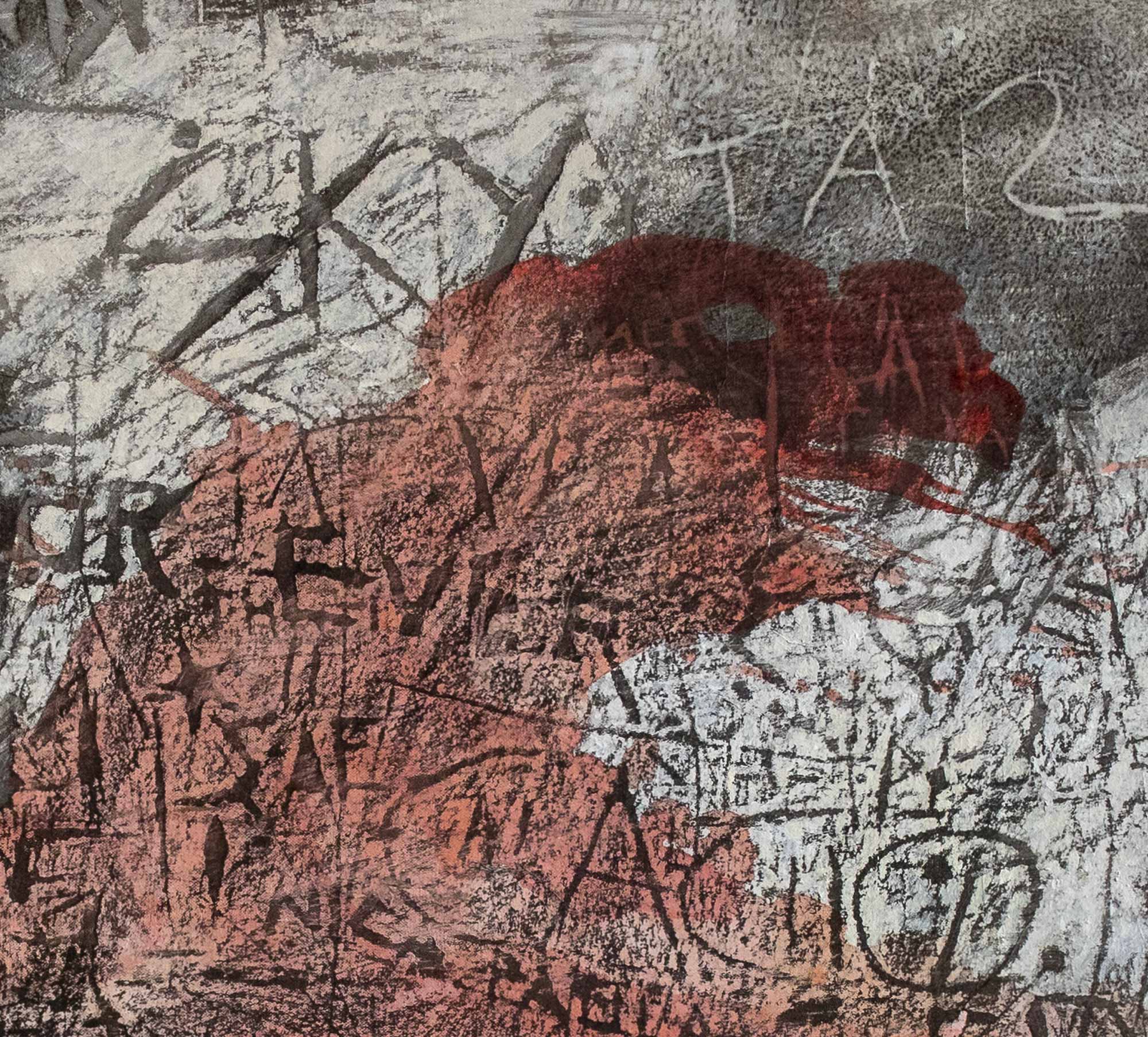

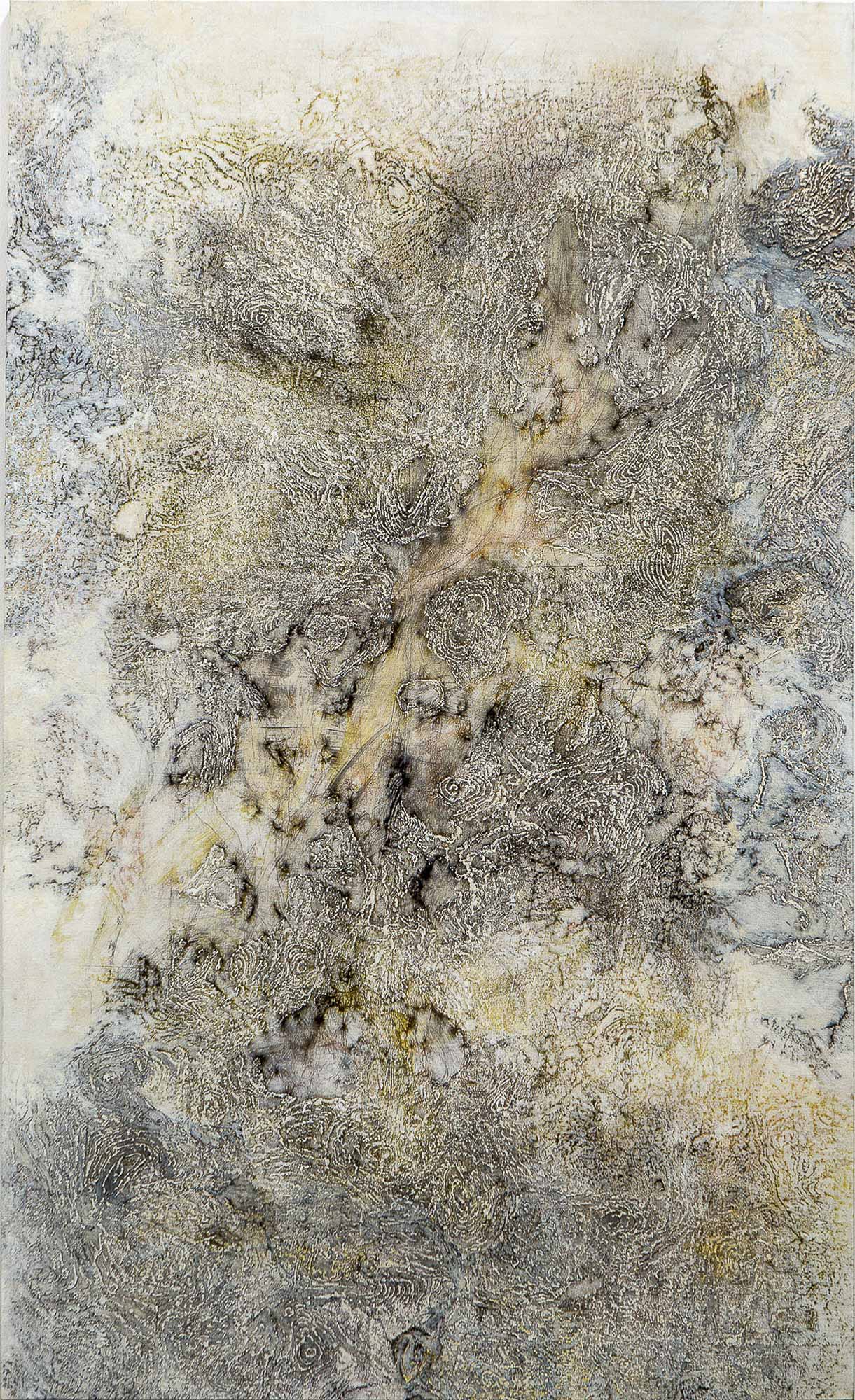

Santa Margarita (2011)

The transfer-prints from the Caffè Rosso at the Piazza Santa Margarita in Venice, Italy, were taken in spring 2009. Since then, many things happened until the idea took shape to use it for the practical problematization of the occidental conventions of representing saints. Traditionally, the church used artists’ and craftsmen’s work to restore the saints’ rights through allegoric representations. The painting depicts the myth of Margaret of Antiochia (a red dragon and a phallic grapheme) in the form of a disembodied allegory of the saint’s legend. It is part of a group of works questioning the representation of sacrality under the limiting condition of profane contemporaneity. Other pieces of this group are Fatima (2010), Sepulchre (2014) and The Altarpiece (2015). Each mark treats a problem that T. W. Adorno described in 1957 as a process in which nothing theological would remain unchanged if it wouldn’t be able to migrate into the sphere of the secular and profane.

Hagiography

Margaret lived at the end of the third and beginning of the fourth century A.D. She is referred to as Margaret the Virgin in the Western church and Marina the Martyr in the orthodox church (East). She was allegedly the daughter of a pagan priest in Antioch but nursed by a Christian woman. After she embraced Christianity herself, her father disowned her. Later the Roman governor Olybrius asked to marry her and wanted that her to renounce Christianity. Upon her refusal, she got tortured. According to the legend, she was swallowed by Satan in the shape of a dragon from which she escaped alive due to the cross she carried that irritated the dragon.

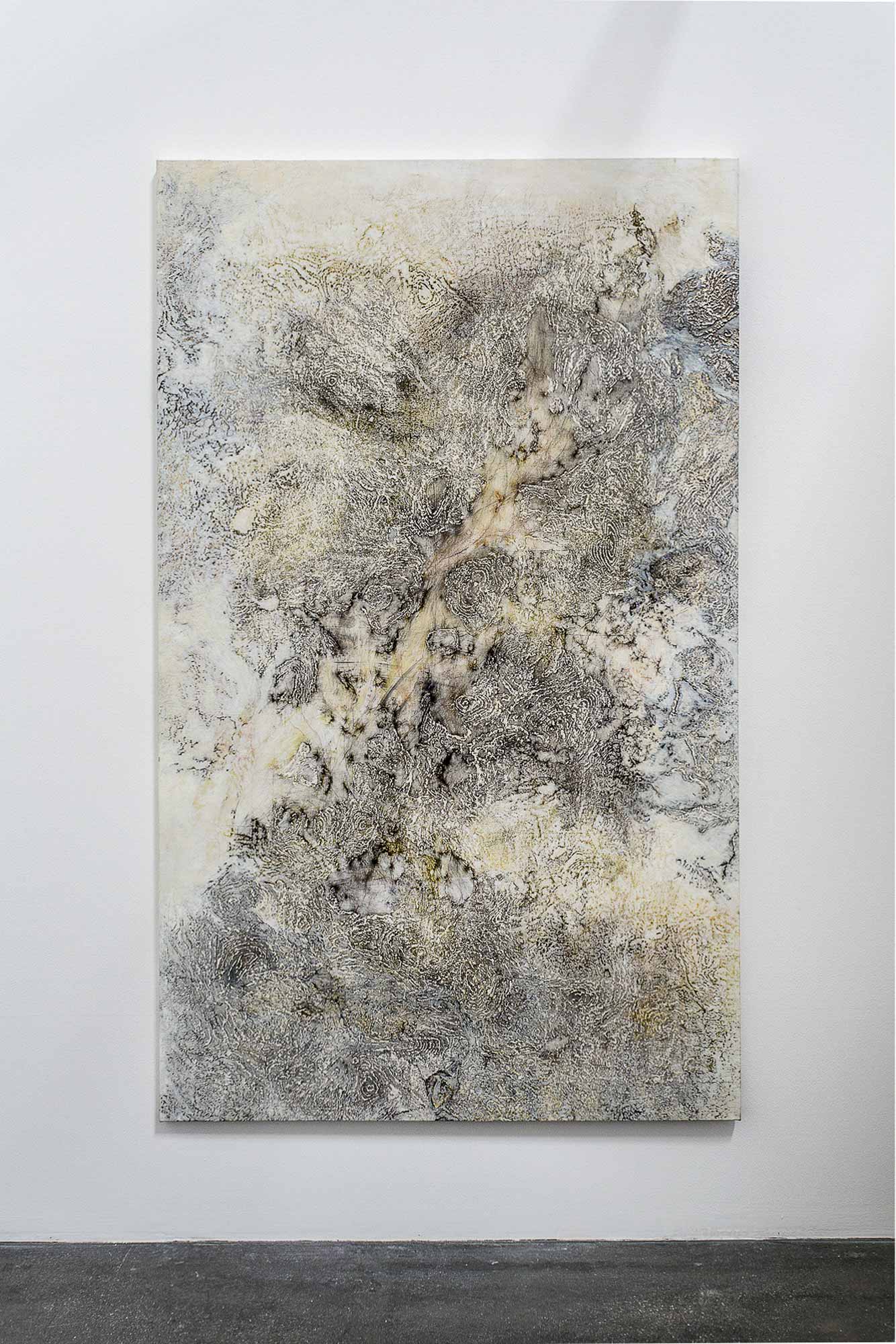

A Short Story of Salt and Sand (2013)

This painting is a transfer print taken from a heavily eroded wall at the railway terminal of El Marsa Beach, a seaside resort in the northern suburbs of Tunis that is visited by many Tunisians. The place is famous for a 500-meter-long promenade that is at least 500 meters short of the beach. Nevertheless, it attracts people from all over the capital, either to enjoy the water and sun during the day or to stroll in the evening. Tunisia has 1,300 kilometers of sandy beaches. After the country declared independence from French colonialism, tourism was discovered as an economic resource and rapidly flourished into a prosperous industry. The beaches became the backbone of the Tunisian GDP. Long parts are now leased to and managed by resorts, spas, and (mostly) European tourist agencies, but a few beaches, such as El Marsa Beach, are still reserved for locals.

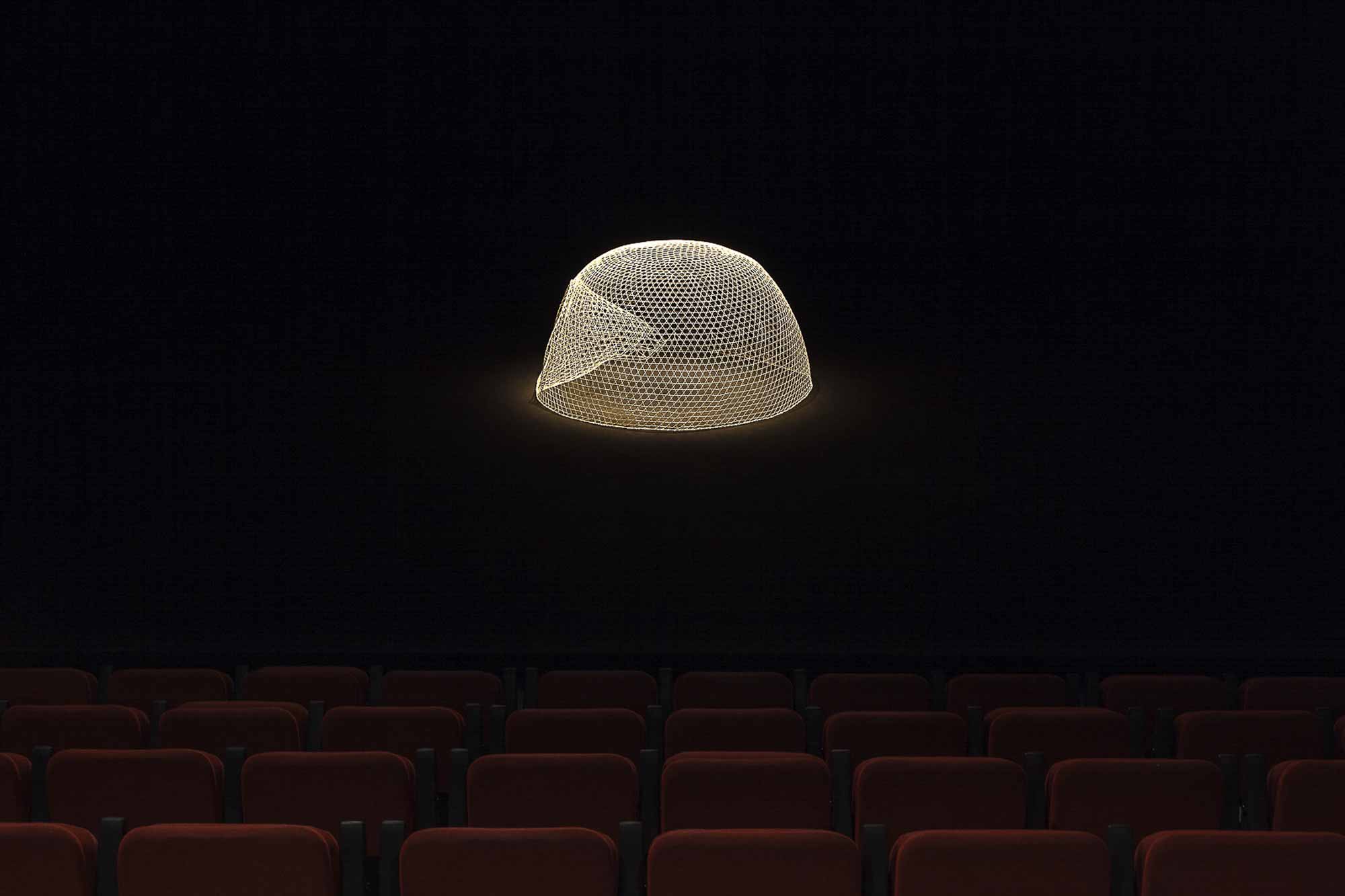

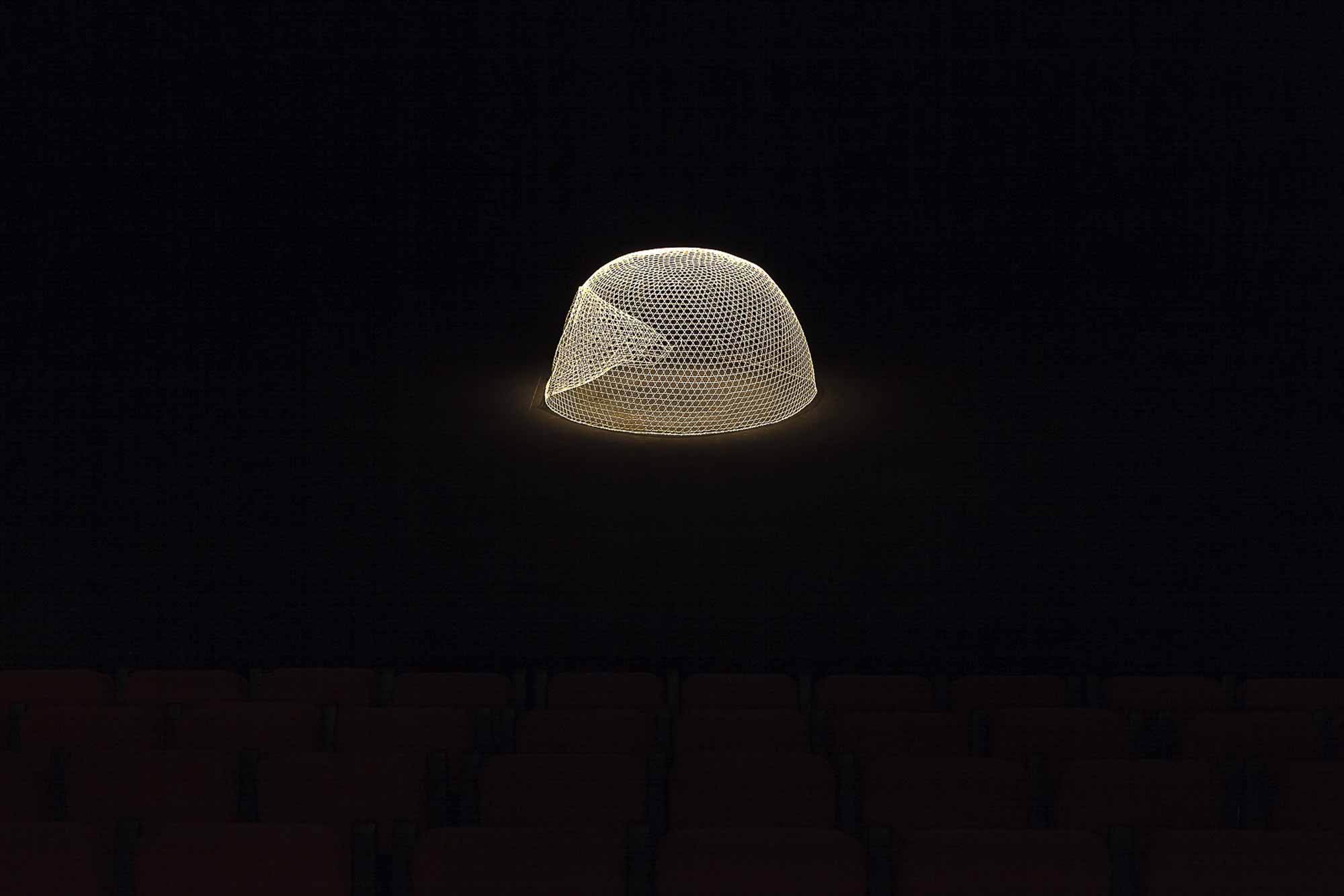

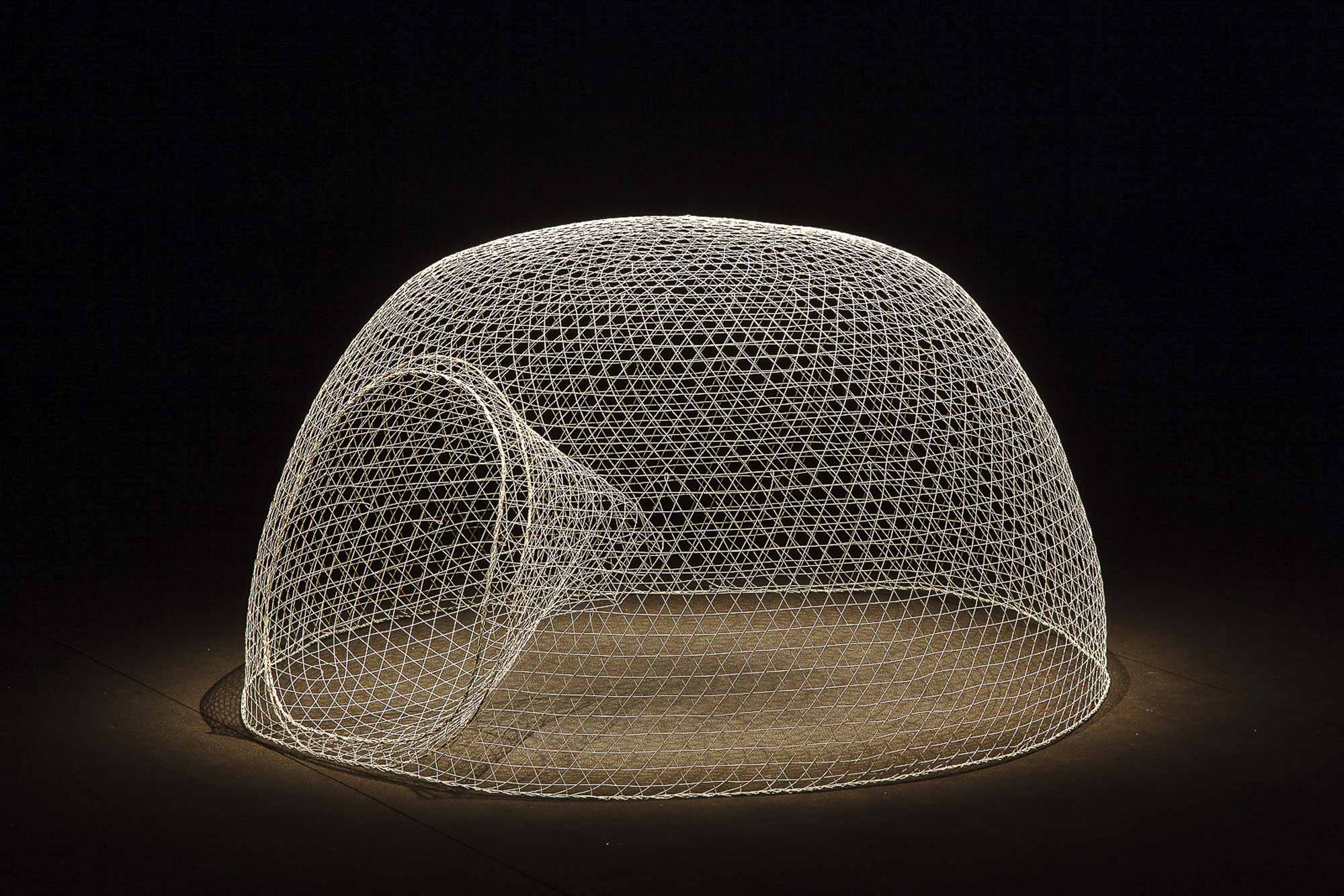

Smooth Criminal (2012)

Smooth Criminal is a sculptural work made from a modified found object: a lobster trap. These are commonly used in the Persian Gulf and are made out of wires that intersect to form the pattern of a six-sided star that, ironically, is also the Star of David. This pattern is invisible to the hungry lobsters that innocently enter, only to realize all too late that they have been ensnared.

The work is a symbol of the political conflict between Israel and Palestine and asks the open questions: Who set up the trap for whom? Was the establishment of the State of Israel itself a trap for the Palestinians as well as for Israelis? And have the futile attempts at a peaceful solution been deceptive, making any tentative escape from the conflict merely illusory?

(Asmaa Al Shabibi)

Tunisian Americans (2012)

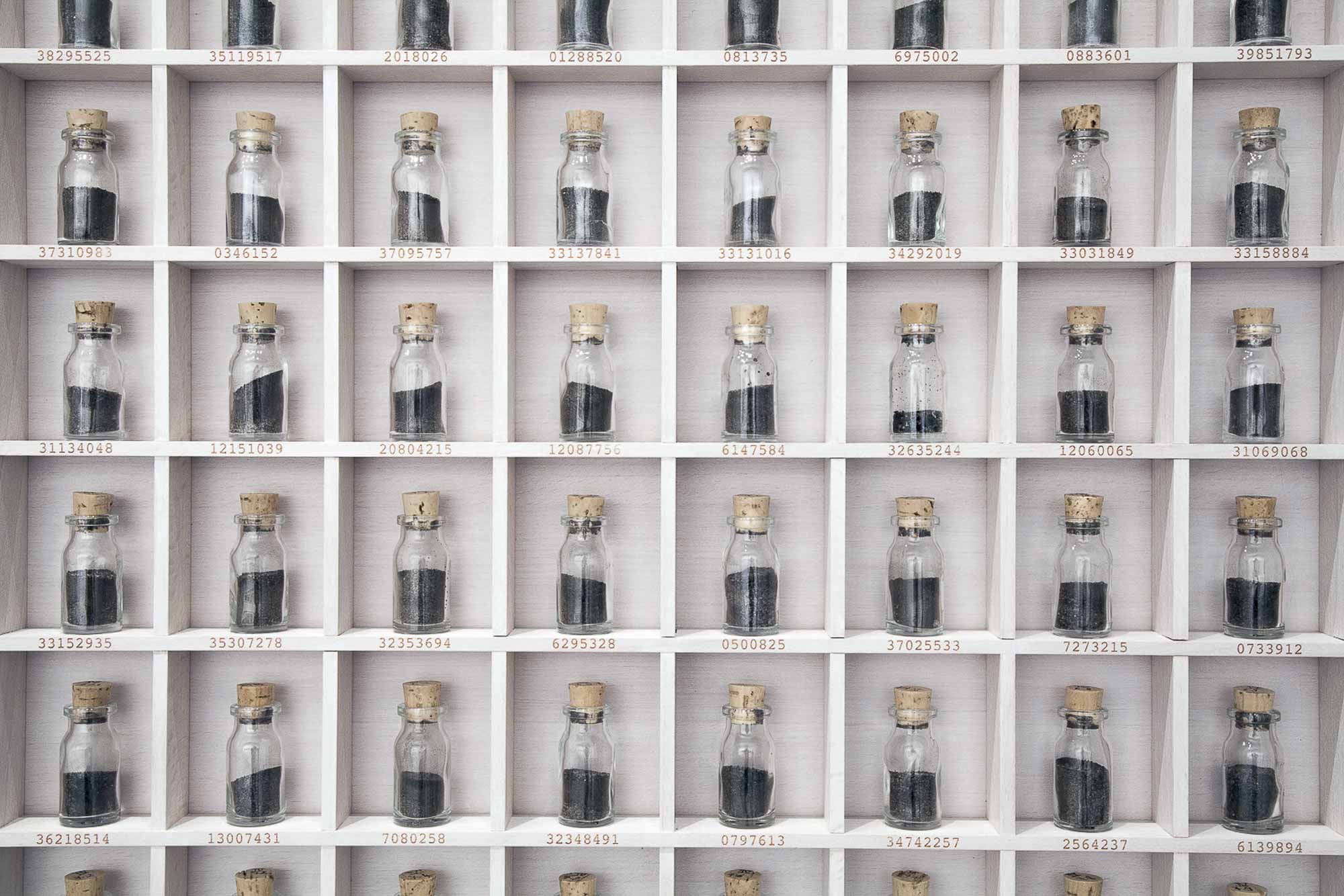

Since type-cases went out of use in the print industry in Germany, they have become a kind of furniture used to manage memories and keep kids’ rooms tidy. For young collectors, they were meant to function as a kind of everyday mini-memorial that fit into each household. However, when I talked to friends who each had one of these Setzkästen, they explained that, rather than preserving the memories of things and events, it helped to forget them. You put them in an empty casket, and you don’t need to think about them anymore.

Four hundred bottles with soil are arranged in four type-cases, in the same order that graves are arranged in the US memorial graveyard in Carthage, near Tunis. Each bottle of earth corresponds to a number, which is engraved on the bottom of the case that shelters it. These numbers are the service numbers of the soldiers and civilians who died during the Tunisian campaign in World War II, from summer 1942 until winter 1943, which means that 2,833 Americans never left Tunisian soil and 3,724 people remain missing to this day. He who lies buried here, fallen for his motherland, lies off the beaten track. Only a few of the bereaved will have undertaken the long journey to mourn by the grave. Not all deaths are equal. Some die and are mourned; others are remembered without names, replaced by a service number.

(Falko Schmieder and Timo Kaabi-Linke, Tunisian Americans, in: The Future Rewound and the Cabinet of Souls, ed. Rachel Jarvis, Mosaic Rooms Editions, London, 2014), pp. 23 – 25)