The Istituto Agronomico per l’Oltremare, now the Agenzia Italiana per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo, was founded in Florence in 1904 with the task of assessing the value and potential of Italian land holdings abroad. The photographic collection consists of 498 photographic albums indicated by country charting from 1913 through the 80s. The photos total 64,336 with the principle collection focused on the period going between the 1920s and 1930s. For this project a focus was placed on the collection with images of Eritrea, Somalia and Ethiopia, between 1937 and 1939.

Since its invention, photography has long been praised for its tendency to neutrality and its ability to accurately render a scene in objective and impartial manners. Such assumption on the objectivity of the photography can be true if one only judges it from its mechanics, as there is always a broader context beyond the frame of the camera itself. Such is the case for the photo collection in the archives of the formerly known as Istituto Agronomico per l’Oltremare.

Although this photo collection had an intended purpose to scientifically document the resources, landscape and products of the newly conquered colonies in Africa, this collection is more than just visual representation. It provides insight into the racializing practices of the fascist regime in the Italian colonial period from which these images emerge, a topic that is too often overlooked in Italian contemporary society. In 1861, Italy became a unified nation-state. With this newfound nationhood came the pressure to catch up with pre-existing global powers like England and France, who had already spread their empires to the African continent and were reaping the economic benefits. This sense of lagging behind, gave birth to the so called first colony, Eritrea, in 1889. Yet, the desire for imperialist expansion did not stop there. After the invasion of Somalia in 1908, Libya in 1911 and Ethiopia in 1935; the fascist regime declared the birth of the Empire of Africa Orientale Italiana in 1936.

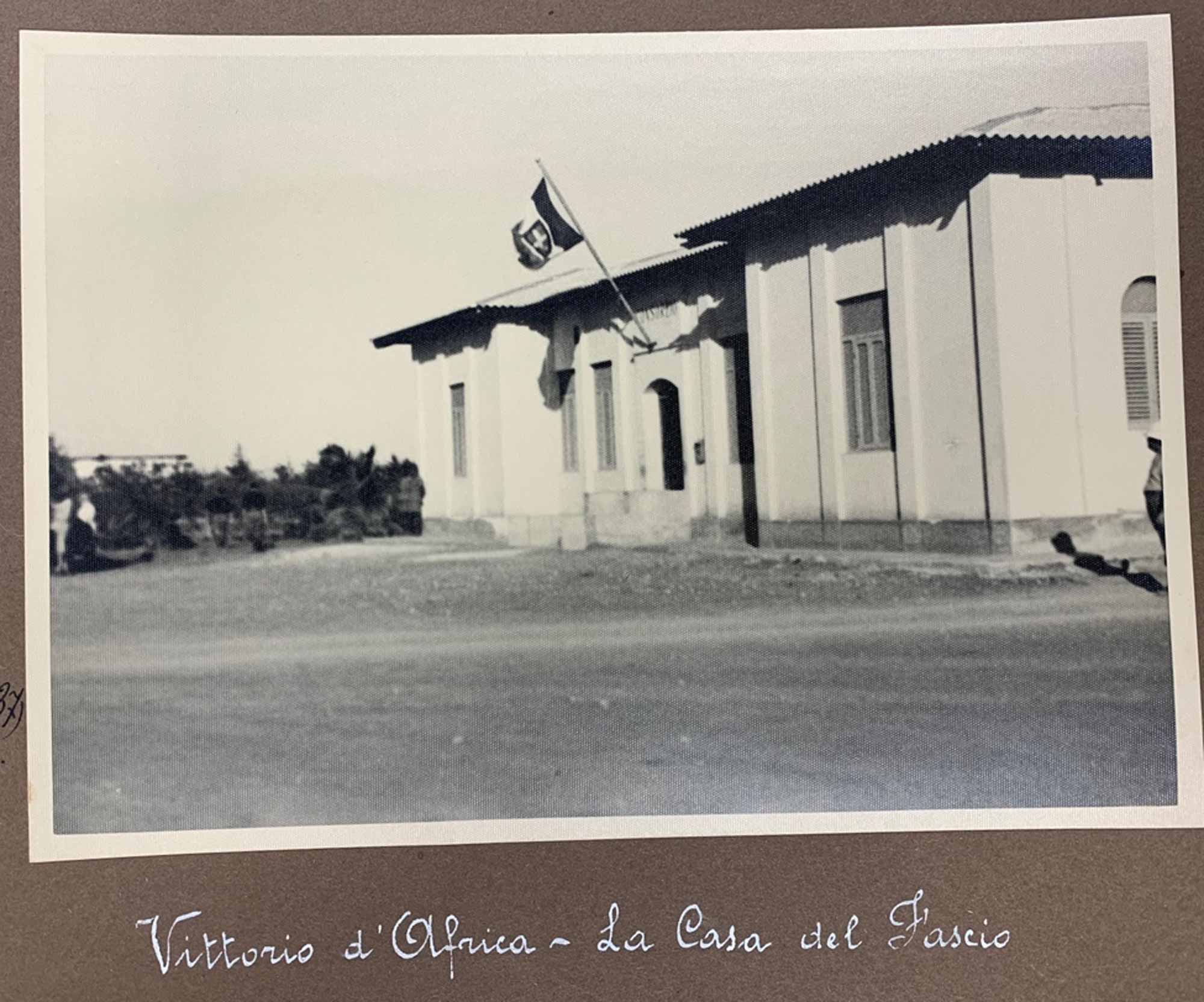

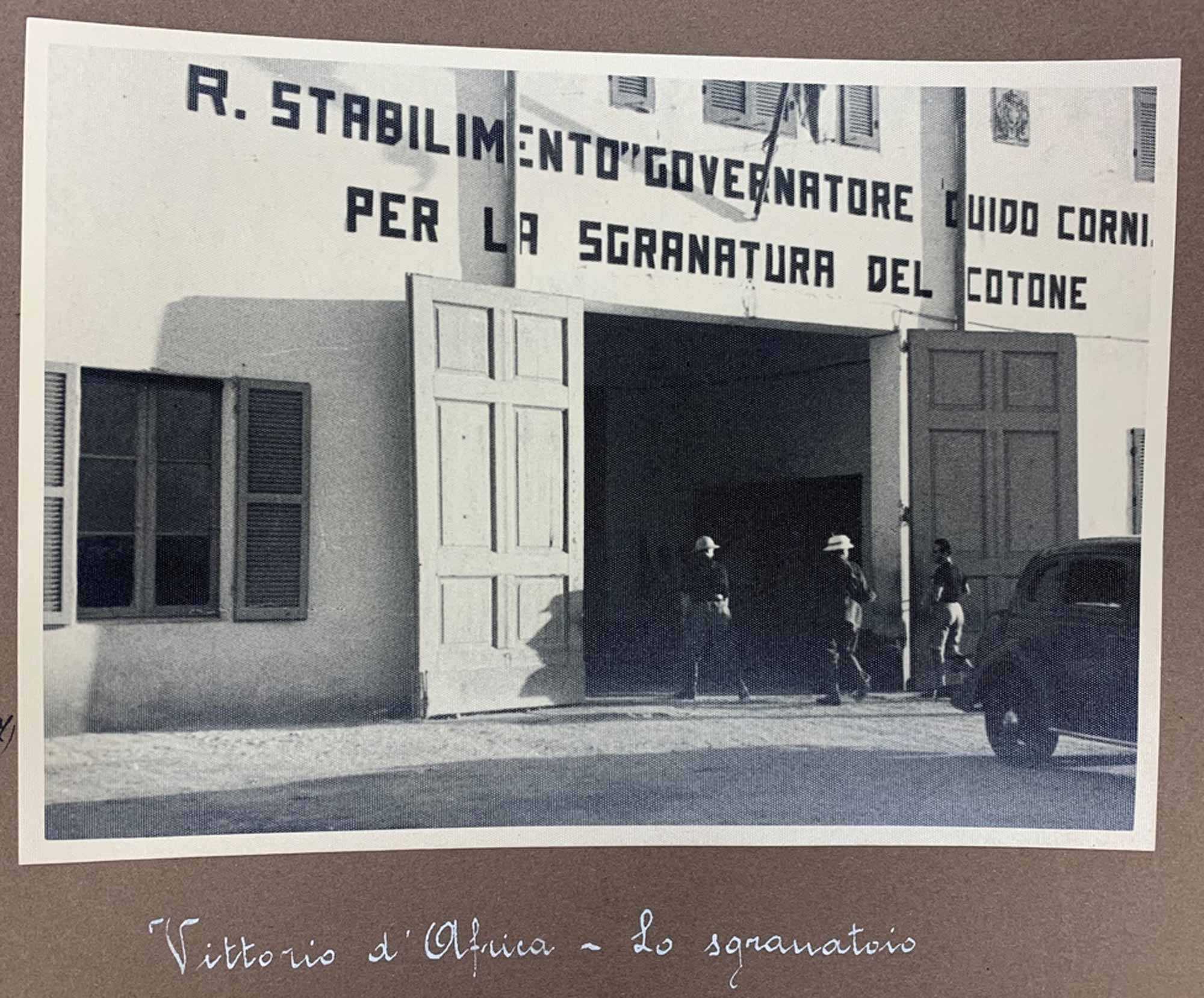

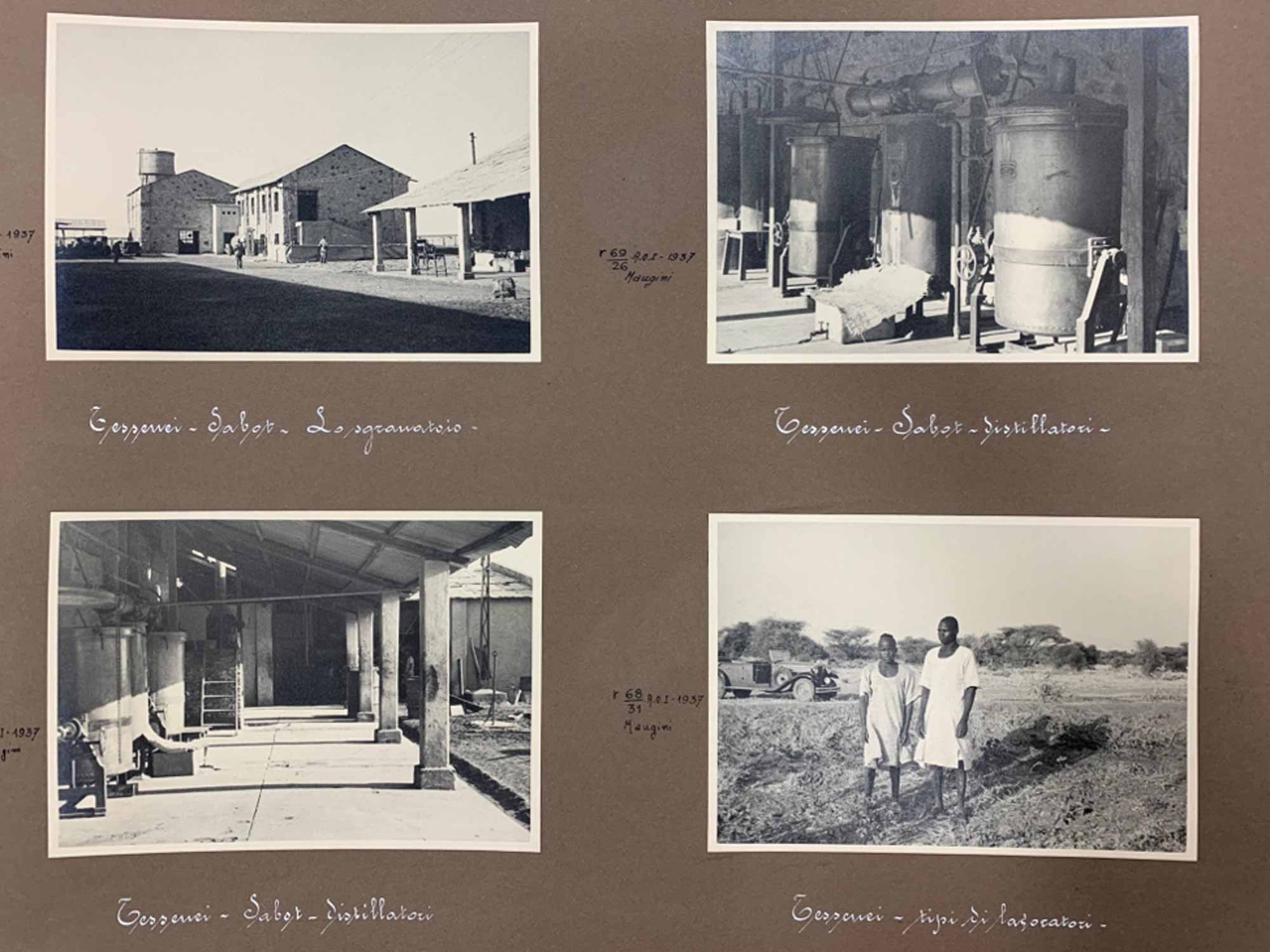

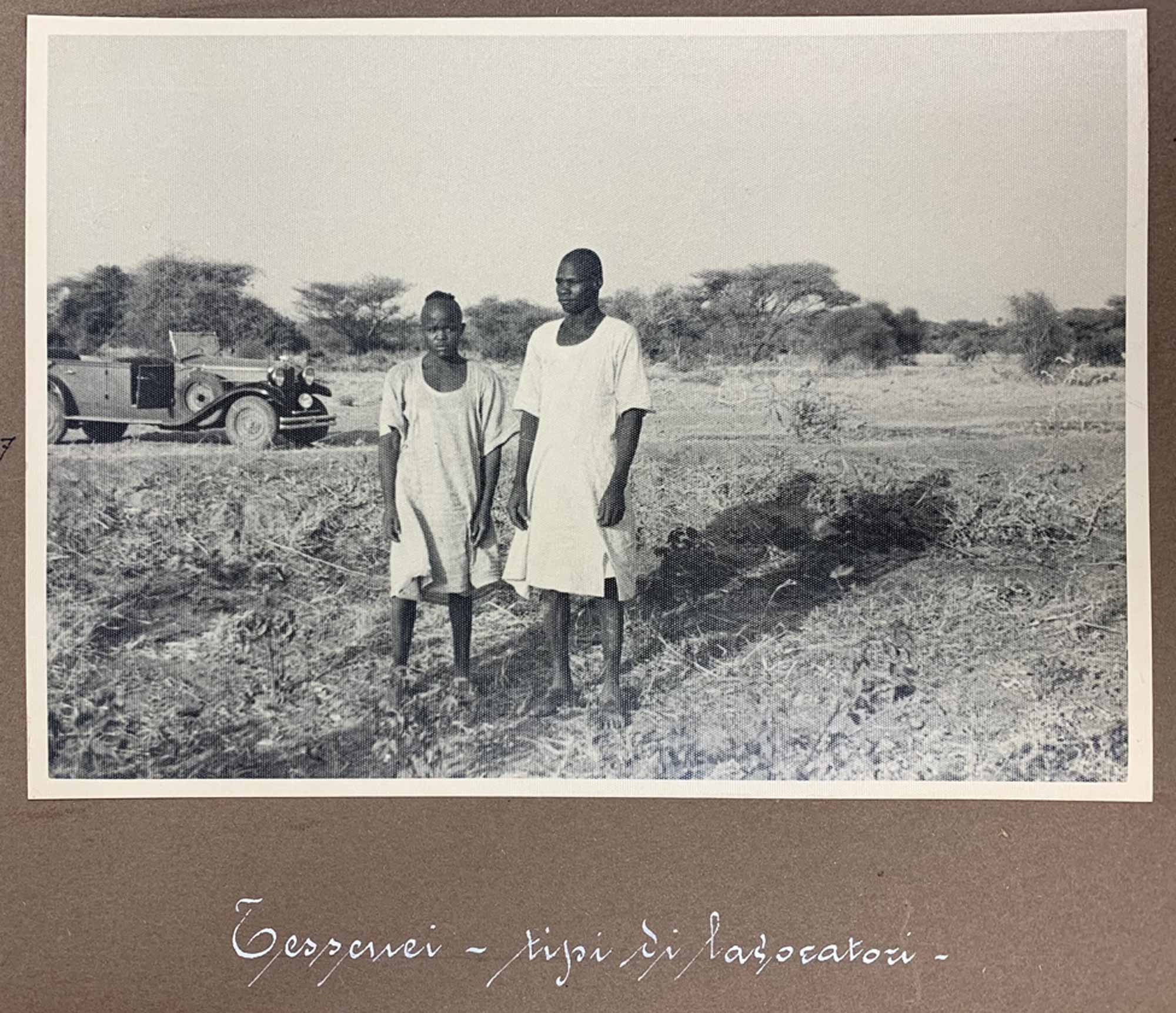

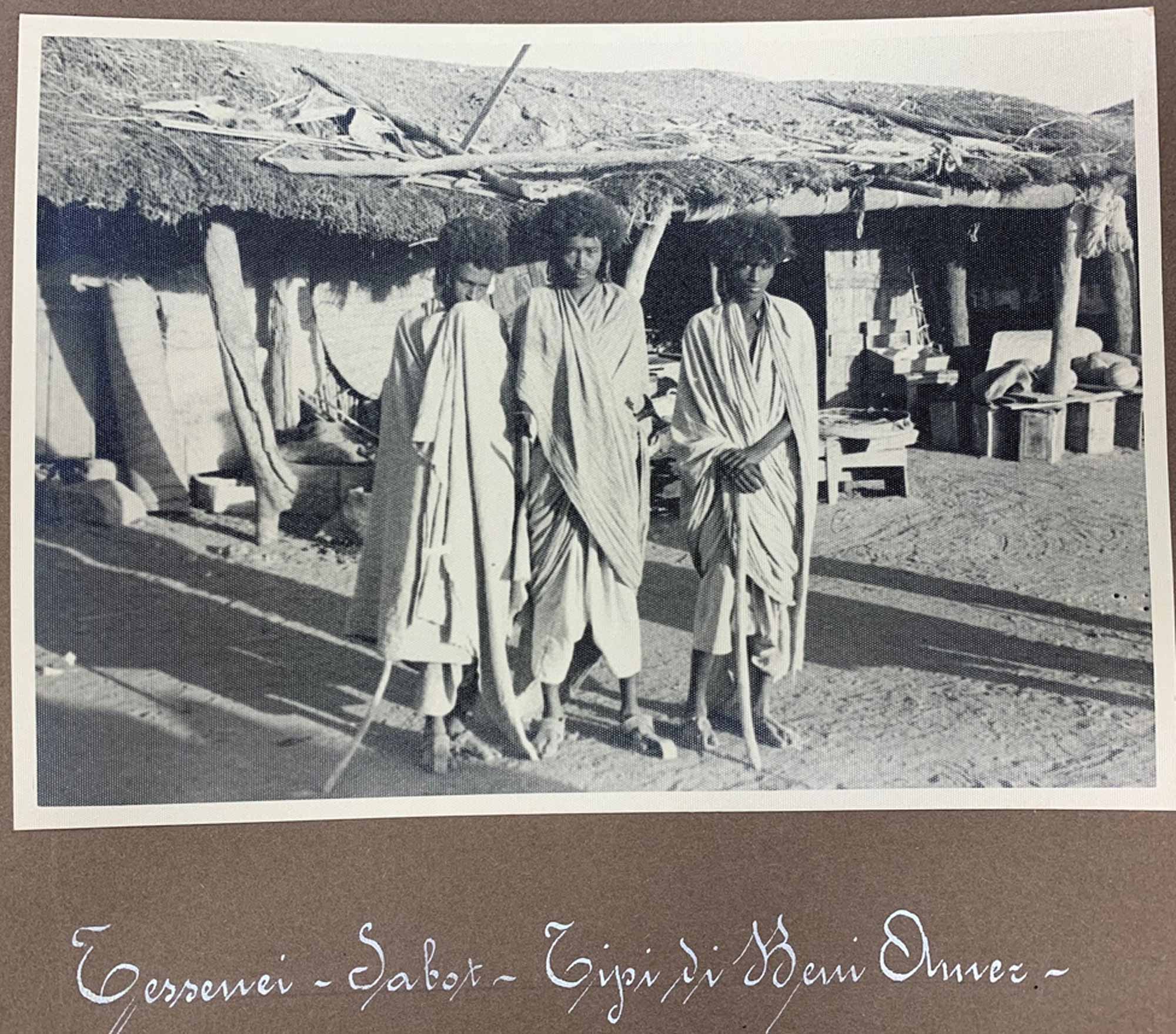

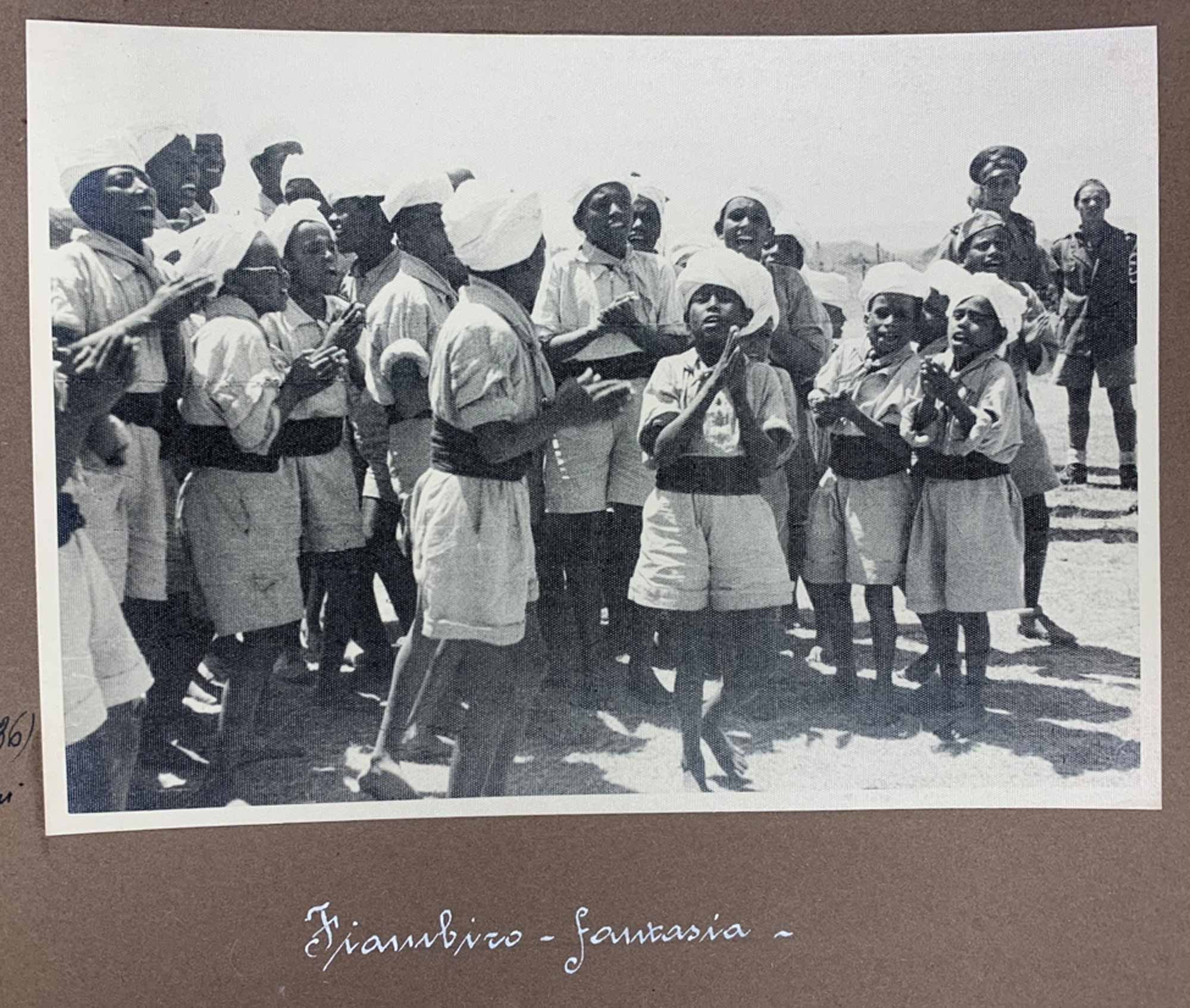

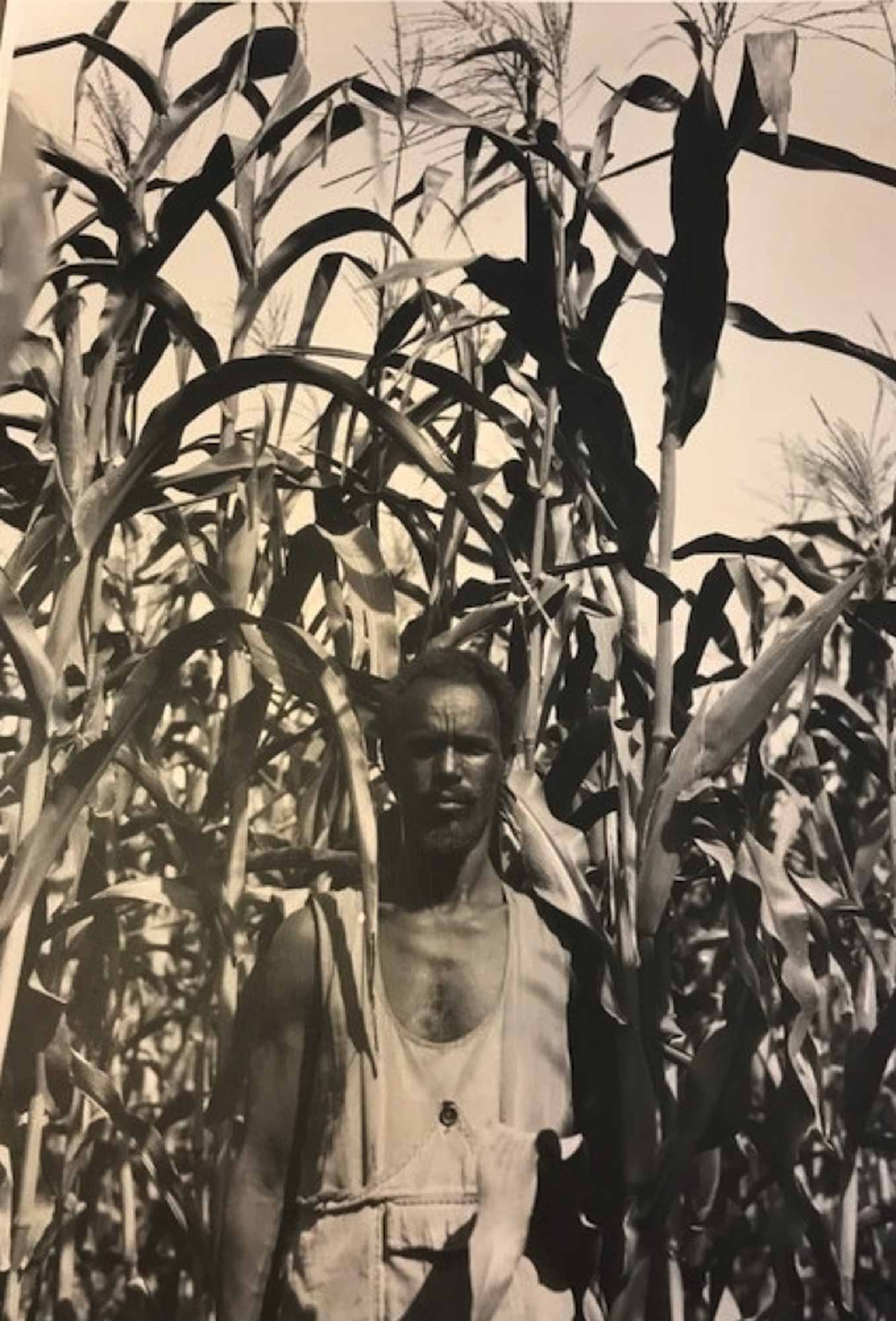

The fascist gaze travelled towards the Empire to capture not only the newly found resources but also the new settling society. The pictures taken were used to show the strength of the Empire and to propagandize the people and agricultural resources in East Africa, in order to lure the Italian public to join the imperialistic cause. Through the lens of this cause, we are able to observe the way African people, as well as environmental resources, were commodified and exploited by the fascist regime with the aid of dehumanizing propaganda.

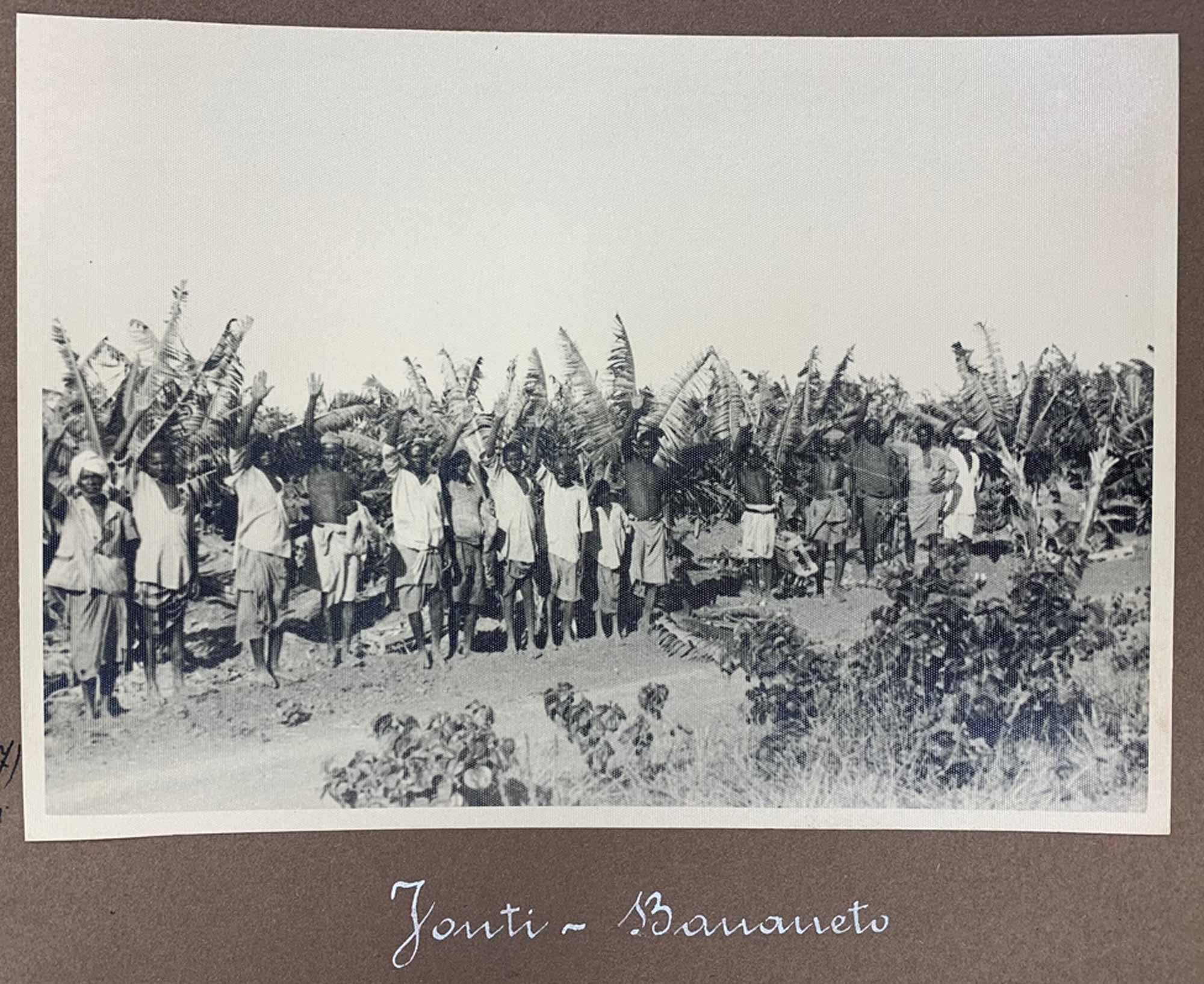

The history of the commodification of Black bodies in the former East-African colonies is an extensive one. Advertisements for the so called colonial goods often depicted Black people in exploitative manners by rendering these bodies synonymous with the marketed products themselves, and a mere tool for economic gain. It is for this reason that when we look at images taken by the Italian fascist regime in East Africa, we must do so critically. The images shown perfectly exemplify the attitudes and the motives of the Italian fascist propaganda. It is not until we consider the history of commercialization of Black bodies that we can discuss the hidden meaning behind these and other images of this sort.

The selected images from the archive present three dominant themes:

1) a direct and inseparable integration of figures into landscapes

2) a dominant glance that visually locates colonial agents and Africans in hierarchical manners

3) scarce visual separation between African people at work, and the local flora and fauna.

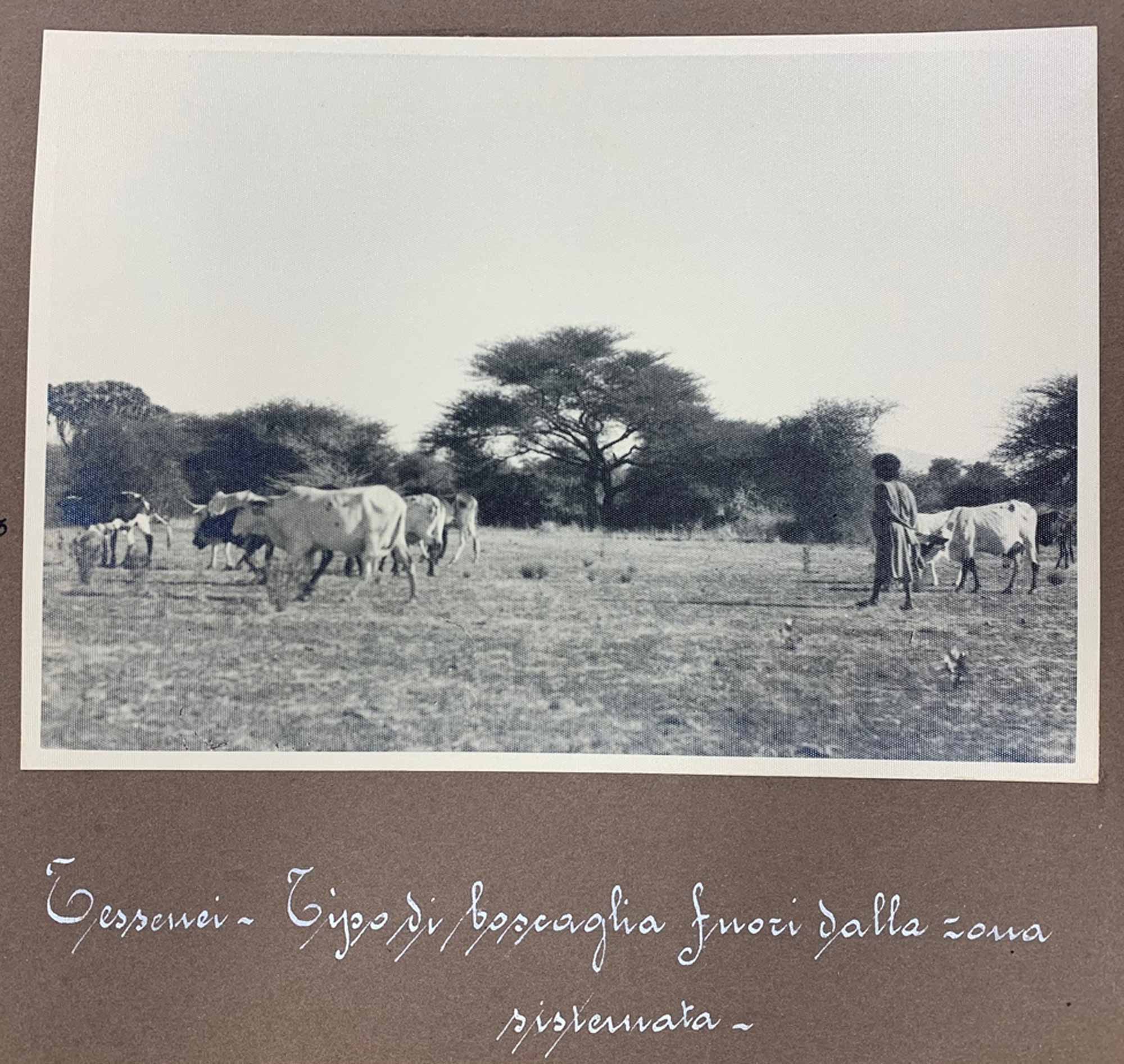

In several images we see no separation between Africans and the cotton/livestock that they tend to. Both the people and the agricultural activities are the focal point of the photographs; neither is the background nor the foreground. This lack of differentiation is no coincidence. Whether unconscious or not, the photographer sees all within the frame as goods and the portrayal of these people are framed as a means of capital gain.

A common justification for imperialism was the idea that non-white, non-Western cultures were somehow inferior and in need of civilization. Through this conceptual manipulation, supported also by racist scientific discourses, several Western nations have claimed an alleged superiority on the Other while justifying their greed-driven usurpation of land, life, and goods through the dehumanization and commodification of Black bodies. In these images, captured to incentivize the support to the fascist colonial project, one may notice the humanity and the individuality granted to White Italians in contrast with the dehumanisation and invisibility of East African populations, depicted as blending in with the local flora and fauna.

Images like these become crucial when we discuss the racializing practices and racism that still occurs in Italy today. Addressing the consequences of racism is dependent on a re-examination of Italian colonial history and the acknowledgement of a need for change. The photographs at the archive of the Agenzia Italiana Per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo are an important resource for the examination of representation, in a period where the frame of photography portrayed more than it set out to.