by Alessandra Tempesti and Farkhondeh Shahroudi

photo: Rachele Salvioli

CHAHAR BAGH

A Farsi expression referring to the specific layout of a Persian garden, in which the plot is divided into four beds separated by two perpendicular water channels which converge upon a basin or fountain in the centre decorated with ceramics or polychrome marbles. The space is articulated in a perfect geometry, with each part allocated to different types of vegetation and animal species as the reflection of a paradisiacal world.

This is one of the figurative schema most frequent in the so-called “garden carpets”, which are among the most fascinating and recurrent decorative models of the carpets produced in Persia during the reign of the Safavid dynasty (16th-18th century). For Farkhondeh Shahroudi, an Iranian artist who has been living in Germany for over twenty years, the carpet represents the space par excellence in accordance with the ancient symbolism in which its enclosed perfection resembles a corner of paradise. In her sculptures and installations the carpets are mobile gardens. They are heterotopic spaces because they have a different spatiality which, on the one hand frees the imagination, and on the other embodies the sense of not belonging that characterises the condition of the artist in exile.

photo: Rachele Salvioli

HETEROTOPIA

The French philosopher Michael Foucault distinguishes between utopias and heterotopias. While the former are fundamentally unreal and consolatory spaces, the latter can be identified with places that actually exist but are heterogeneous and sometimes disquieting, such as cemeteries, hospices and psychiatric clinics, but also ships, theatres, museums, libraries and colleges. They are, rather, localised utopias which insinuate a substantial discontinuity into the continuum of space, creating an illusory space that, in effect, makes the spaces we live in even more illusory. For Foucault the garden is the most ancient example of a heterotopia: “the garden is a carpet in which the whole world enacts its symbolic perfection, and the carpet is a garden that can move across space.”

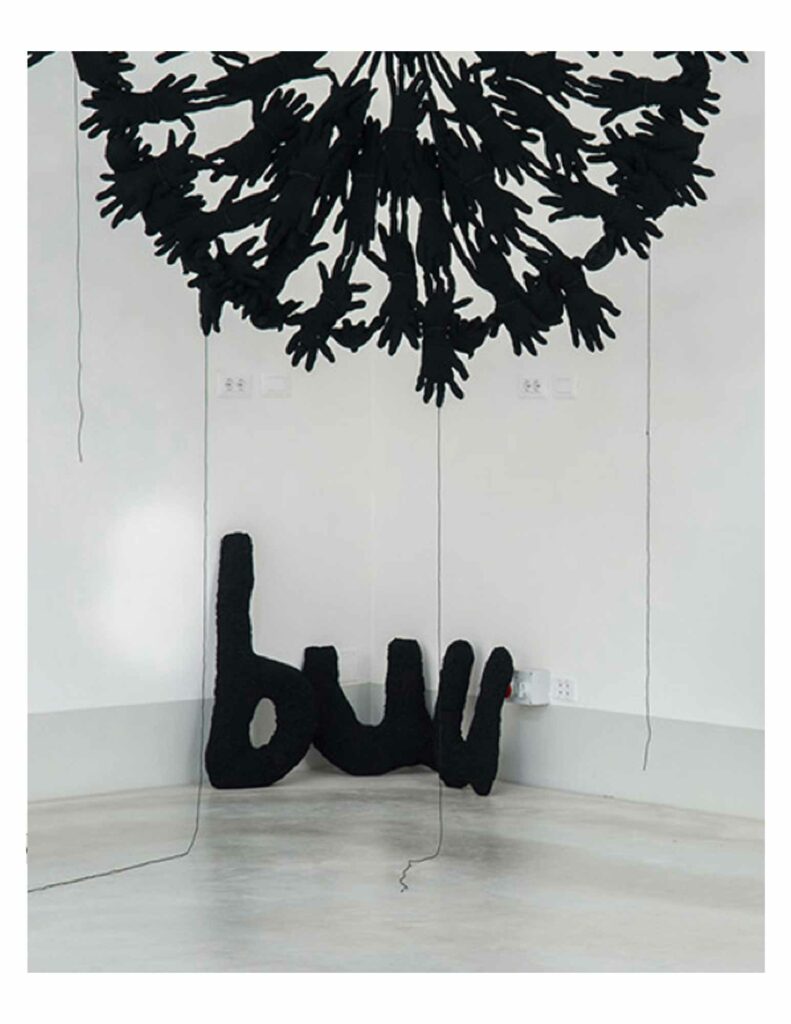

In Me Giardino (Me garden), a work produced for the artist’s solo exhibition at Lottozero textile laboratories, the circumscribed space of the carpet, dismembered and then recomposed, becomes a self-portrait, hooked brutally to the ceiling but still capable of movement. It is a catalysing hub that attracts the scattered fragments of the artist’s poetic language disseminated all around: the anthropomorphic animal and vegetable sculptures, suspended in the air or speared to the ground or, again, leaning against the walls next to her three-dimensional onomatopoeias of wonder, concrete poetry that all languages share.

photo: Rachele Salvioli

ONOMATOPOEIA

The imitation, using vocal and written language, of non-verbal sounds such as noises, animal sounds, exclamations and so forth. Onomatopoeia creates new words by imitating the sound of the referent animate or inanimate object: these are transparent words where the connection between meaning and sound becomes explicit.

Poetry is one of the main sources of Farkhondeh Shahroudi’s artistic research. Poetic language is transformed into her plastic matter, such as the sculptures made from hand-stitched fabrics. The three-dimensional exclamations (these too padded and stitched) become sculptures to all effects and purposes. They are phonemes of astonishment alluding to the degree zero of poetry (and sculpture) where it is the sense of wonder that reveals the creative process of the imagination, overturning accepted contents and symbolism.

The artist simply continues to reinvent her language, or rather the languages in which she practices poetry: Farsi and German.

PALIMPSEST

An ancient parchment manuscript on which the original writing has been erased, by scratching or decolouration, to be replaced by a new text, often arranged crosswise to the previous one. This practice was common above all in the Middle Ages (between the 7th and the 11th century) using parchments dating to the 5th and 6th centuries.

When she writes in Farsi, Farkhondeh Shahroudi uses textile materials to create artist’s books with loose pages, foldable and pliable like the fine membranes of parchment. As in those ancient artefacts, here too the artist employs a stratified script, laying words and phrases over each other until they become illegible, like a palimpsest laden with memories but by now indecipherable.

photo: Rachele Salvioli

GLOSSOLALIA

A linguistic phenomenon that consists of speaking in an unintelligible language using non-existent words and sounds, emotional outbursts and neologisms. It also refers to the state of ecstasy in which people pray to the gods in a mysterious language. This practice is common to various religious ambits, even quite remote from each other, such as shamanism, Hellenistic mysticism and primitive Christianity. Glossolalia is a creative activity: building a verbal language which, in its constant changing and proliferation, cancels the distinction between form and content.

From an initial condition of aphasia, the inability to express herself in a language not her own, the artist arrived at the invention of a language of her own in German. This was achieved through a process of automatic writing using the left hand, leading to the creation of a series of works – this time on paper – in which the words expand freely over the page in time with physical respiration.

photo: Rachele Salvioli

A poetic movement that emerged in England and America in the early twentieth century, in which the image was taken as the basis and substance of poetry rather than an accessory ornament. The manifesto, signed in 1913 by the poet Ezra Pound, confirmed the intention to use an exact, essential and objective language “made of real things”, to reject superfluous words and metaphors and to employ free verse: “imagism is vivid presentation not representation.” Farkhondeh Shahroudi has always written poetry; text and language are the raw materials of her creation, from which the image takes shape. Whether it’s automatic writing deliberately slowed down by the choice to use her left hand in her work on paper, or Persian letters that are illegible due to the overlapping of the graphic signs, she seeks to create, with language, a space of attraction for images, totally irrespective of the two-dimensionality of the poetic text and the three-dimensionality of the sculpture.

photo: Rachele Salvioli

HYPHA

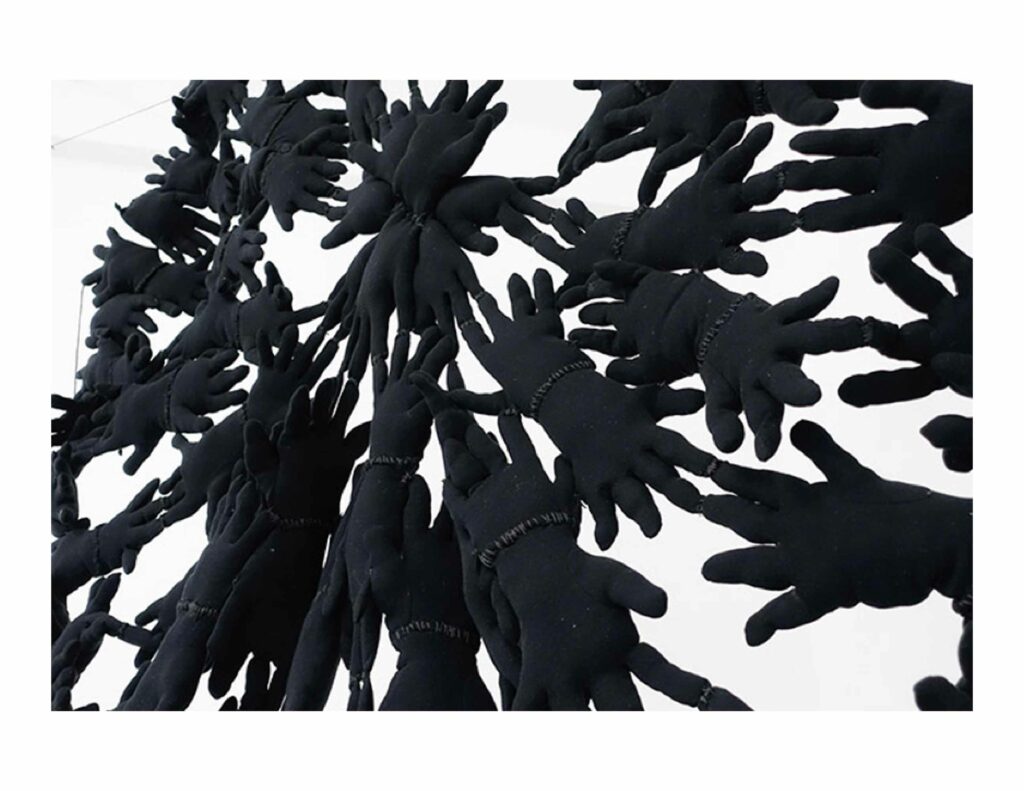

One of the unicellular or multicellular filaments which, when placed one above another, form the ramified and threadlike structure that makes up the mycelium, the vegetative body of a fungus. The term derives from the Greek hyphe, meaning weaving, web (in Aristotle, “the spider’s web”). Hypha by Farkhondeh Shahroudi is a web of hands within which the gaze is caught.

Despite having a multiplicity of references, it functions first and foremost as an image in its own right, neither representative nor symbolic. It is the etymology of the word that instead reveals the architecture of the artist’s poetics, made up of interconnected spaces and meshings of meaning, like a woven texture (from the Latin texere) which is also the root of the poetic text (textus).

photo: Rachele Salvioli

photo: Rachele Salvioli

TEXTUS

Past participle of the Latin verb texere: to weave, construct. Text has a textile and reticular nature, and the very etymological root of the word brings us back to an act of weaving in which words, phrases and concepts are brought into relation and charged with meaning.

For Farkhondeh Shahroudi text and textile are the same thing. The seams on the sculptures are primary signs; the aleph, the first letter in the Arabic alphabet, is a simple vertical line, like an “I”, as are the hairs that cluster in dense skeins in the artist’s recent works. All the stitching is made up of these lines, like original signs underlying different languages and alphabets, neutral signs to be used to mould one’s own poetic universe.

photo: Rachele Salvioli

OU

In modern Persian the third person singular (ou) is neuter and can indicate either female or male gender. In almost all Indo-European languages the neuter has been progressively absorbed by the masculine. However, leaving grammar aside, it can be found in other fields of knowledge, such as politics, botany, zoology, physics and chemistry. OU is the title of a video work by Farkhondeh Shahroudi in which the pronoun, written in Persian characters, progressively invades a fixed image alluding to a figure wrapped in a chador, anatomically ambiguous like all the artist’s sculptures (it is, in actual fact, part of a foot inside a black sock).

If transposed beyond the realm of language, the category of neuter becomes a new paradigm: it becomes the other of the choice, the other of the conflict. Like the flags that the artist makes out of various materials (carpets, hair or interwoven fabrics), which are neutralised to the point of becoming Antiflags, banners supported on simple iron rods or bamboo canes, stripped of ideology, de-territorialised, capable of crossing (or flying over) any place or country.

photo: Rachele Salvioli

FLYING CARPET

A magic accessory at the service of the legendary hero: this is the realm of pure wonder present in Arabic and Persian mythology and in Russian folklore. Only later did it arrive also in the West with Galland’s translation of the One Thousand and One Nights.

In her essay “Il flauto e il tappeto” Cristina Campo constantly asks herself why the carpet flies. Flying Carpet flies because it is a slingshot with a projectile wrapped in a carpet. This ancient weapon of hunting and war is shown lying on the ground as if it had just been left there by some gigantic being, possibly a god. In the Arabic language the word for “butterfly” and that for “carpet” share the same etymological root, but the latter flies “because it is spiritual terrain, and the designs of the carpet [here again, a garden carpet] announce that terrain.” These are territories that are always located elsewhere for the artist far from home, inscribed within the symbolic frame of the Persian garden that contains the infinite spaces of the poetic imagination.

@ 2017 Artext