Ala Younis is a research-based artist. Collaboration forms a big part of her practice, as do curating and joint book projects. Using objects, film and printed matter, Younis often seeks instances where historical and political events collapse into personal ones. She holds a BSc. in Architecture from University of Jordan and MRes in Visual Cultures from Goldsmiths, University of London. She is a recipient of the Bellagio Creative Arts Fellowship, as well as two art prizes from Cairo Youth Salon (2005) and Jordanian Artists Association (2005). She is co-founder of the publishing initiative Kayfa ta, on the advisory board of Berlinale’s Forum Expanded, and member of the Academy of Arts of the World (Cologne). https://kayfa-ta.com/

Al-Bahithūn [the (re)searchers]

Painted plastic, oil pastels and carbon transfer on paper, found objects

Dimensions variable

2018

This project investigates oil as an engine for knowledge production, exploring the impact that its nationalization in Iraq had on intellectual and academic life there. It condenses the movements of oil revenues across the nationalized schemes of research support in Iraq, and looks into their reminiscence in film, art and architecture. The research is titled after a 1978 Iraqi film in which a group of men are hired to journey south in search of oil. After much adventure, they stumble upon the Rumaila oil fields, which were nationalized few years earlier, the real promised land, whose riches, now entirely under Iraqi control, far exceed those of myth. The strange tractor-like vehicle moored next to floating architectural structures equipped with telecommunication technologies that would allow the searchers communicate with their administration. When they are informed with the good news of sitting on a bed of oil, three men had defected from the group already to look for what they treasure, before they are brought back to realize that the nationalized oil fields is their only real and modern treasure.

Modern flats in high-rise buildings, plots of land, customs exemptions on Mercedes sedans, as well as scholarships and book materials were part of larger scheme of incentives offered by the state to young scientists and graduates to ensure they work in Iraq after completing their education. This building up local knowledge as well as the technical and industrial expertise was necessary to maximize oil profits, but was also coined as a national asset.

Working on site for the oil companies would afford more than these benefits, and with the pay checks, the workers in oil received a literary magazine that carried the same name. Edited for a while by Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, the magazine saw the emergence of much of Iraq’s modern literature, poetry and artistic projects.

An issue from 1963, features a ceramic mural by Nuha Al Radi that was commissioned by Iraq Petroleum Company to don its office in Baghdad. Al Radi made a grid of ceramic tiles on which the names of Iraq oil fields (Arab and Kurdish regions) were inscribed in Arabic letters next to many warm suns that matched those that radiate over the oil fields. Al Radi made another mural in the 1980s, on Haifa Street close to the high rise buildings dedicated for the Iraqi researchers and graduates, and before that a sculpture on the brains the stem out of Mercedes cars around the streets of Baghdad. From 1991, she detailed the dystopia of living in Baghdad under the threat of the gulf war and ensuing blockade, including how she saw nightmares of American soldiers stationing on Haifa Street, or having to fake an illiteracy statement for herself to exit from Iraq at some point, when a ban on graduates movement was in function. Haifa Street became a battle site after the fall of Baghdad in 2003.

Commissioned in the context of Crude, curated by Murtaza Vali, Jameel Art Centre, Dubai, 2018

Drachmas

Painted acrylic, plastic, polystyrene, metal and wood

dimensions variable

2018

This work draws on television stagecraft and the architectural vernacular of model making to consider the emergence of the Arab daytime TV dramas and the dramatic interplay of actors and events that conspired to shift centres of cultural production and political power. Far from an account of a master plan, the story of daytime television Arab drama began in the 1960s and the industry quickly forged a network across the region and developed numerous genres set against backdrops of small village life, Bedouin culture, the glory of Islamic history, as well as ancient pre-Islamic times, espionage, the Palestinian resistance and solidarity, and the modern household and way of life. Inside a studio, interior and exterior scenes were made from painting fake walls, installing props, making up actors, and putting up conversations. It was possible to produce a fake desert inside a studio and make a couple move down between its dry bushes, while spectators follow willingly on the couple’s conversation. Reproduced exteriors and interiors in studios made way for large numbers of cast and crew not just to move between Beirut, Amman, Baghdad, Cairo, Athens, Kuwait and Ajman studios, but also to navigate war, evade boycotts, save small capital despite currency devaluations, and amasse a great popularity, in a time that was continuously going through political predicaments.

Concurrently, the video cassette recorder (VCR) entered the home and enabled households to record their favourite programming directly from their televisions, turning everyday people into accidental archivists and living rooms into homegrown archives. Younis has accessed these personal collections and created over 40 small-scale models based on scenes from well-known dramas, bringing viewers in for a closer look. This clinical reproduction of the scenes abstract the relationship to specific social, political, cultural and geographic references, while highlighting the studio as a place of modest means but prolific production.

High Dam (Red Rose)

2018

A 45-min lecture performance that presents clips from two films, as well as other materials that expose the making of regimes of truth through interventions made in the script of the released I’m against the rejected one. 2016-ongoing.

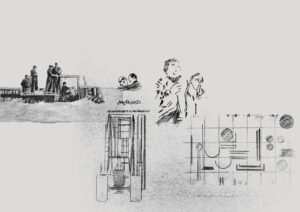

In the 1960s, Gamal Abdel Nasser hinted that ‘al-magnon’ (Youssef Chahine) should make return to UAR to make films again. Chahine accepted a commission to direct the first UAR-USSR co-production: a 70mm colour Cinemascope feature film on the High Dam project in Aswan. Chahine made not one but two films. The People and the Nile was shot as the building works were taking place; but when the edit was finished in 1968, it was rejected. Chahine readapted the work to be approved as a new film that would fit the two states visions and was released in 1970. In the 1990s, Chahine stated that, in the process of the Soviet Union’s disintegration, he could admit “without fear” to having “stolen a copy” of the first, censored, version of the film. He released it in 1997 under the title Once Upon a Time… The Nile.

Two literary works by Sonallah Ibrahim also focus on the High Dam project: a novel that is the negation of the mystified truth of a documentary reportage. Sonallah Ibrahim wrote Star of August (1973) novel based on the truer chronicles of his and two colleagues’ trip to the high dam site in 1966, in which they jointly published a dense state propaganda reportage, The Man of the High Dam (1967), that was highly allegorical, mystified and uninformative of the work hardships. Ibrahim moved to study cinematography in Moscow following the publication of the reportage, but his second work on the High Dam was written between 1966 and 1973; banned in Egypt, the work was published in Damascus. Ibrahim was member of a Marxist political group, led to his imprisonment from 1959 until 1964, when he received a pardon on the occasion of Nikita Khrushchev visiting Egypt for the diversion of the Nile.

This project was presented in several editions in talks and exhibitions in Boston, Berlin, Amman, Cairo, San Sebastian and Prague. In its lecture performances, (factual and audio-visual) elements from the reverse paths of two creative works on the High Dam offer an insight into the processes that governed the politics of the era, particularly the propaganda apparatus of the UAR and the USSR, and the tricks Chahine resorted to when his work did not fit its producers’ vision.

Presented in High Dam: Modern Pyramid at VI PER in Prague (2020), the show presented the commissioned work The Friend of Nubia (2020), which is a model of the expedition vessel Sadiq en-Nuba (The Friend of Nubia) that served as the floating base for the five Czechoslovak expeditions in Nubia. The catamaran was constructed in the Holešovice shipyards from disused military pontoons and subsequently dismantled and shipped to Egypt, where it was reassembled – similar to some of the Nubian temples at the time. The model thus also experiments with the possibilities of reassembly. The catamaran was designed by the boat captain Milan Hlinomaz and anecdotes from his book Plavba za hieroglyfy (Sailing to the Hieroglyphs, 1967) inspired the series of embroideries. Parallels between archeological and military campaigns are striking: not only did the expedition receive equipment from the Czechoslovak army, but the Czechoslovak Institute of Egyptology at Charles University in Prague and Cairo was established in 1958 in part as a consequence of the 1955 arms deal.

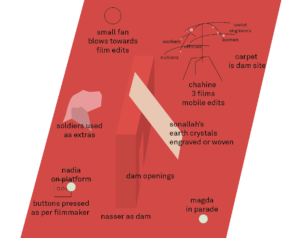

The Aswan High Dam also became a site of the propaganda apparatus of Egypt (from 1958 to 1971 known as The United Arab Republic, UAR) and the USSR, which governed the ways in which the dam was depicted in film and literature, such as in the works of Youssef Chahine and Sonallah Ibrahim. The Chahine Mobile and Posters (2019) compare scenes in the various versions of the film directed by the Egyptian film director Youssef Chahine and commissioned as the first UAR and USSR co-production to promote the construction of the dam. Inspired by the kinetic sculptures of Alexander Calder, the mobile is an abstraction of the various elements of each of the three versions of the film, suspended in the air and changing configurations triggered by the blowing of a Soviet fan – representing the propaganda and censorship apparatus governing the editing processes. The Sonallah Model (2020) refers to the Egyptian Marxist writer and former political prisoner Sonallah Ibrahim and his literary works based on his stay on the construction site. The Button Box (2019) symbolises the 1964 ceremony in which the Egyptian President Nasser and the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev pressed the button that diverted the Nile from its ancient riverbed into a canal, allowing for the next stage of the construction to begin. While Youssef Chahine caught this moment on film and even gave signal to Nasser and his international guests, Sonallah Ibrahim was on the occasion of Khrushchev’s visit released from his imprisonment. The redirecting of the Nile also meant the beginning of the rising water level, slowly but surely flooding the Nubian villages and archeological sites. The series of prints Mobilities (2020) captures some of the ensuing movements of both material, such as the relocated temples and the construction material, as well as humans, including the displaced Nubians and the construction workers.

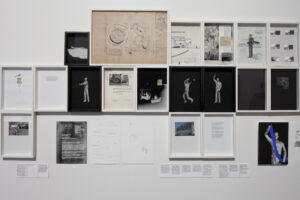

Plan for Greater Baghdad

Two- and three-dimensional prints, drawings, archival and found materials, and models.

2015

This project was activated by a set of 35mm slides taken by architect Rifat Chadirji in 1982 of a Gymnasium in Baghdad that was designed by Le Corbusier and named after Saddam Hussein. The project looks at monuments, (by) architects, (for) governments, and the shifts and tensions between ideals and ideologies.

The Saddam Hussein Gymnasium metamorphosed through numerous iterations of plans over twenty-five years before it was inaugurated in 1980. Up until then, the commission for the Gymnasium passed through five military coups; six heads of state; four master plans, each with its own town planner; a Development Board that became a Ministry and then a State Commission; a modern starchitect among a constellation of many others with their associated architects, draftsmen, contractors, agents and lawyers; local architects accompanied by similar structures from their own consulting firms, from government departments, and from parallel commissions; more than one local artist/sculptor; eager competitors; and other monuments that simultaneously appeared and disappeared as a result of these same conglomerations.

Heavily based on archives, found material, and the stories of its protagonists; Plan for Greater Baghdad looks into protecting monuments for posterity, and into performing plans for Baghdad as an expression of power or as a necessity. Missing from the representations and citations contained in established archives, the images that document the performances of design, power, and designing power are pieced together from fragments of other images and from records of gestures retrieved from representations and narratives by local artists.

Produced as a set of motions and signals enacted by characters frozen in the denouements of historical time, the three-dimensional depictions pertaining to the men who appear in the Plan for Greater Baghdad, and the interventions into existing documents culled from various archives, produce a dual-layered timeline that pits developments in the Gymnasium story against those in Baghdad.

Elements in order of appearance in the research for this project: Le Corbusier. Concrete structures. Master plans. Iraq’s negotiated oil revenues. Other projects by modern architects for Baghdad and the region. The archives of others and Iraqi archives. The interests and fates of Heads of States. Deputies to Heads of States. Rifat Chadirji, his Iraq Consult, and his peers. Statues and monuments. The Stadium versus the Gymnasium. Jewad Selim. The Tigris River and its meanderings through Baghdad. Palm groves, helicopters, informants, doubles and film productions.

A new iteration of the project, Plan (fem.) for Greater Baghdad (2018), places the contributions made by female artists, architects and other influential characters within the development of Baghdad and its modern monuments. The work rearticulates archival material to bring about new narratives. In this case, the reading sees beyond the male dominance of the city’s architecture and politics, as well as the grand narratives.

Produced with support from The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) and Sharjah Art Foundation. Part of research developed during Bellagio Creative Arts Fellowship (2013) and an Ashkal Alwan residency (2011).

Plan for Feminist Greater Baghdad

Two- and three-dimensional prints, drawings, archival and found materials, model.

2018

A new iteration of the project, Plan (fem.) for Greater Baghdad (2018), places the contributions made by female artists, architects and other influential characters within the development of Baghdad and its modern monuments. The work rearticulates archival material to bring about new narratives. In this case, the reading sees beyond the male dominance of the city’s architecture and politics, as well as the grand narratives.

Produced with support from The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) and Sharjah Art Foundation. Part of research developed during Bellagio Creative Arts Fellowship (2013) and an Ashkal Alwan residency (2011).