by Roy Brand

In a letter Sigmund Freud wrote to his friend, Arnold Zweig, after the latter returned from a trip to Eretz Yisrael (Palestine) in 1932 he expressed his views of the Holy Land in an enchanted but frustrated voice: “How weird must it have looked to you … This tragic, crazy land Just think, this piece of land is not connected to any progress, to any discovery or invention. Palestine did not produce anything but religions, holy madness, and vane attempts to overcome the external world of appearances by means of the internal world of the wishes. And we ourselves come from there; our forefathers lived there maybe five hundred maybe one thousand years … and you cannot tell what heritage we carry in our blood and our nerves from this land … Ah, life could have been so much more interesting had we known that.” 1

Should we suggest that after seven decades of experimentation, one major catastrophe, and at least seven full-fledged wars, Israelis now know what heritage they carry in their veins? And could we suggest that they might learn to see who they are and what they have become by reflecting on the products of art and other creative acts of expression — what Walter Benjamin (another heretical Jew) called the organs of the collective?

The troubled relations to a homeland that Freud expressed were never resolved. The establishment of the State of Israel only gave a home to homelessness. Of course, Israel is the home that the Jewish people craved for many generations, but it is a problematic one — to say the least. It is a new-old country that offered resettlement for millions of refugees and immigrants, while at the same time creating a new refugee problem and bringing destruction to the livelihood of hundreds of thousands of others. It is a place that came to represent the loss of home, and to cover for that loss it had to be reconstructed as both more and less than what it was: more because it was a mythic ideal or a utopia of milk and honey; and less because it seemed as if it had to be emptied of its concrete reality and turn blind to its local Palestinian population. This prompts a set of questions inherent to the current generation: How do we construct an individual and collective identity that admits one’s foreignness to one’s home, the only home Israeli-born people know? How can one feel at home when it is alienated, endangered, not really one’s own, and perhaps not even wanted? How can one live in such exile at home?

A related problem is that of collective identity, or the very idea of collectivity, which is one of the most highly praised values of Israeli society, from its inception in the pioneer settlements and the kibbutzim to today’s groups of young Israelis roving through India or South America in postmilitary trips. Again this situation gives rise to several questions: What room is there for individuality alongside the adhesiveness of tribal collectivity? How can one be different while belonging, or be apart while also being part? And what source of significance can one find outside the collective, which simultaneously sustains and erases one’s individuality? Contemporary Israeli art allows for an exploration of a wider notion of collectivity and home—as two sources of meaning to which Israelis do not comfortably belong. Artists such as Michal Rovner, Sigalit Landau, Guy Ben-Ner, Yael Bartana, or Ahlam Shibli, different in many other respects, share an attitude towards home and collectivity that focuses on their deficiency or loss. In other words, their work reflects a peculiar mixture of intimacy and estrangement. This is what Freud captured with the notion of the uncanny; Unheimlich, a condition of estrangement that occurs when the familiar turns unfamiliar. The uncanny marks the moment of transition from the familiar to the strange. Freud notes the fact that, uncanny in itself, that the feeling of home and feeling of not being at home, are easily interchangeable. He concludes, quoting Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, “unheimlich is the name for everything that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light.” 2

Of course, this is not only an Israeli theme. Even at present artists and cultural theorists, philosophers and public intellectuals debate — sometimes quite vigorously — on the notions of space, place, and home. Questions of national and cultural borders are of course at the forefront in a country whose borders are not agreed upon, but ideas of belonging and of being apart; the search for meaning in a defunct social and cultural environment are all global questions. Being an Israeli artist just gives them a sharper edge. The local context is not local anymore, but more like a crystal representation, a condensed environment that allows for a focused look at what affects the rest of the world. To render this debate concrete, this essay will try to take the reader on a virtual tour of Israel: visiting the new display of the Israeli Art wing in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, and a few artist’s studios.

The first permanent display of Israeli art opened in the newly renovated Israel Museum in 2010. This exhibition can serve as a contrast to the main theme of this essay. While I emphasize the exilic dimension of contemporary Israeli art, the common, official narrative of the Israel Museum focuses on the return of the Jews to the land of Israel and the revival of its original language, culture, and art. According to this narrative, immigrant artists — almost exclusively Ashkenazi men — gradually came to renounce their European background and adopt a new Sabra tonality, which is a more direct, simple, and in tune with the bright light and clean patterns of the land. (3) For example, the new Israeli wing of the museum takes the visitor on a tour that begins with the works of Bezalel teachers from the early twentieth century.

Ze’ev Raban’s Elijah’s Chair and the large sketch for a carpet by Ephraim Moses Lilien are still steeped in European Orientalism. The modernist revival that soon followed includes important paintings by such artists as Nahum Gutman and Reuven Rubin who move us out of the shtetl and into the busy streets of new Israeli towns and villages. There is a certain triumphalism in the march of works on display. Gradually a new sense of individuality emerges, clean from the exilic heritage. The works from the nineteen-fifties and sixties, closer to the establishment of the Israel Museum itself, reach a climax in the paintings of Yossef Zaritsky, Yehezkel Streichman, and Arie Aroch. Following the historical narrative on display Israeli art became more reflective and political after the war in 1967 — exhibiting traumatic or melancholic undertones relating to the loss of a mostly European past. Important works by Moshe Kupferman, Michael Gross, Igael Tumarkin, and Raffi Lavie represent the final chapter in this development with their unique blend of old Jewish sensitivities and new Israeli styles.

In contrast to this narrative of return, revival, and coming to terms, this essay emphasizes the non-linear, indeed conflicting forces that become apparent with the current generation of Israeli artist. The return of the Jews to the land of Israel is indeed a constitutive myth, but a stronger voice insists on the inherent foreignness, or the exilic condition that persists and has intensified. In the following, I wish to consider this exilic condition by following a number of prominent Israeli artists whose work is well known internationally.

I would like to conclude this essay by considering the question of who gets to be called Israeli. Ahlam Shibli, a female artist born in Galilee village in 1970 and living in Haifa, would not like to be included in this piece. She presents herself as a Palestinian living in Isreal. But that complexity, apart from the fact that she is an excellent artist, is just one more reason to consider her work in this exilic context. As a way of registering her resistance, I will not include any images of her work.

Sigalit Landau

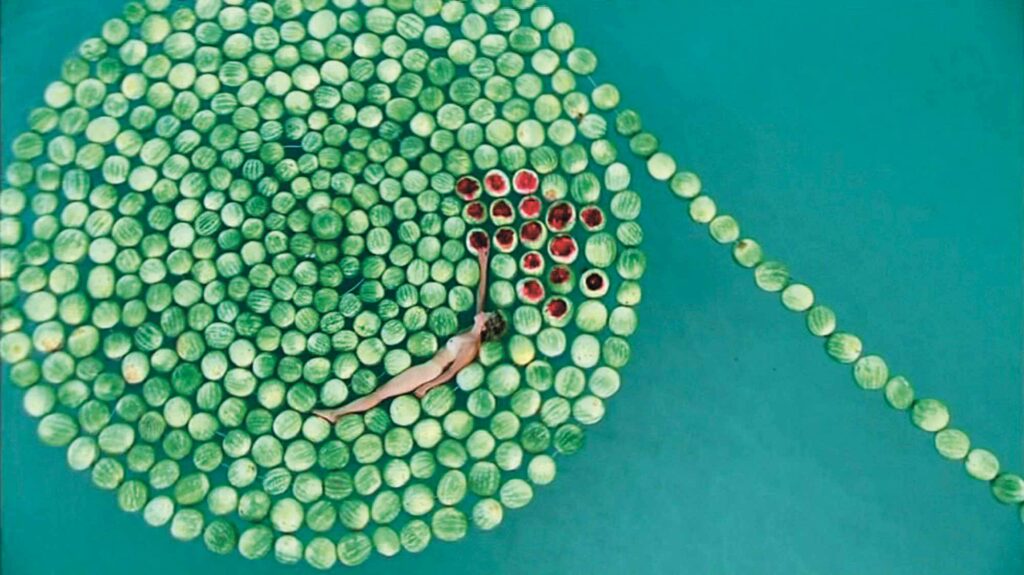

Sigalit Landau’s video, Dead Sea (fig.1) is screened on the floor at the very entrance of the Israeli wing in the Israel Museum. Itzhak Danziger’s iconic sculpture, Nimrod, is erected just before it. The first, a video piece from 2004, shows the female figure of the artist floating naked in the Dead Sea tied to a spiral of watermelons that have been sliced open. The latter, an iconic nineteen-forties sculpture of a Canaanite god carved in Nubian sandstone, is widely seen as representative of the domestication of the land by the new virile and Hebrew speaking inhabitants. Their subsequent positioning is meant to indicate, as if in a glimpse, the grand narrative of triumphant resurrection.

But the slow moving, melancholic pace of Landau’s open spiral seems at odds with the heroic presence of Nimrod. In fact, the spiral, the sea and the salt all seem to reference Robert Smithson’s SpiralJetty (1970). Few people have seen this coil of rocks in a remote bay of the Great Salt Lake, except in handsome, but inevitably misleading photographs. Spiral Jetty hovers like a ghost over the history of art. Its presence is absent. It is, in Smithson’s words a “non-site that exists [in] a space of metaphoric significance.” 4

More recently the spiral became the mark of (non)location in the virtual space of the internet through the @ sign, called a Strudel in Viennese- inspired Hebrew. The spiral then spirals from earth to the heavenly heights of metaphoric significance; the spiral is equally local and ephemeral, concrete and symbolic. Utopia (literally a non-site) is a non-place that cannot be achieved in this world, hence the contradiction and dangers of trying to resurrect it on earth. Landau’s spiral thus undoes the virile monument next to it as it unravels from confinement to release.

Michal Rovner

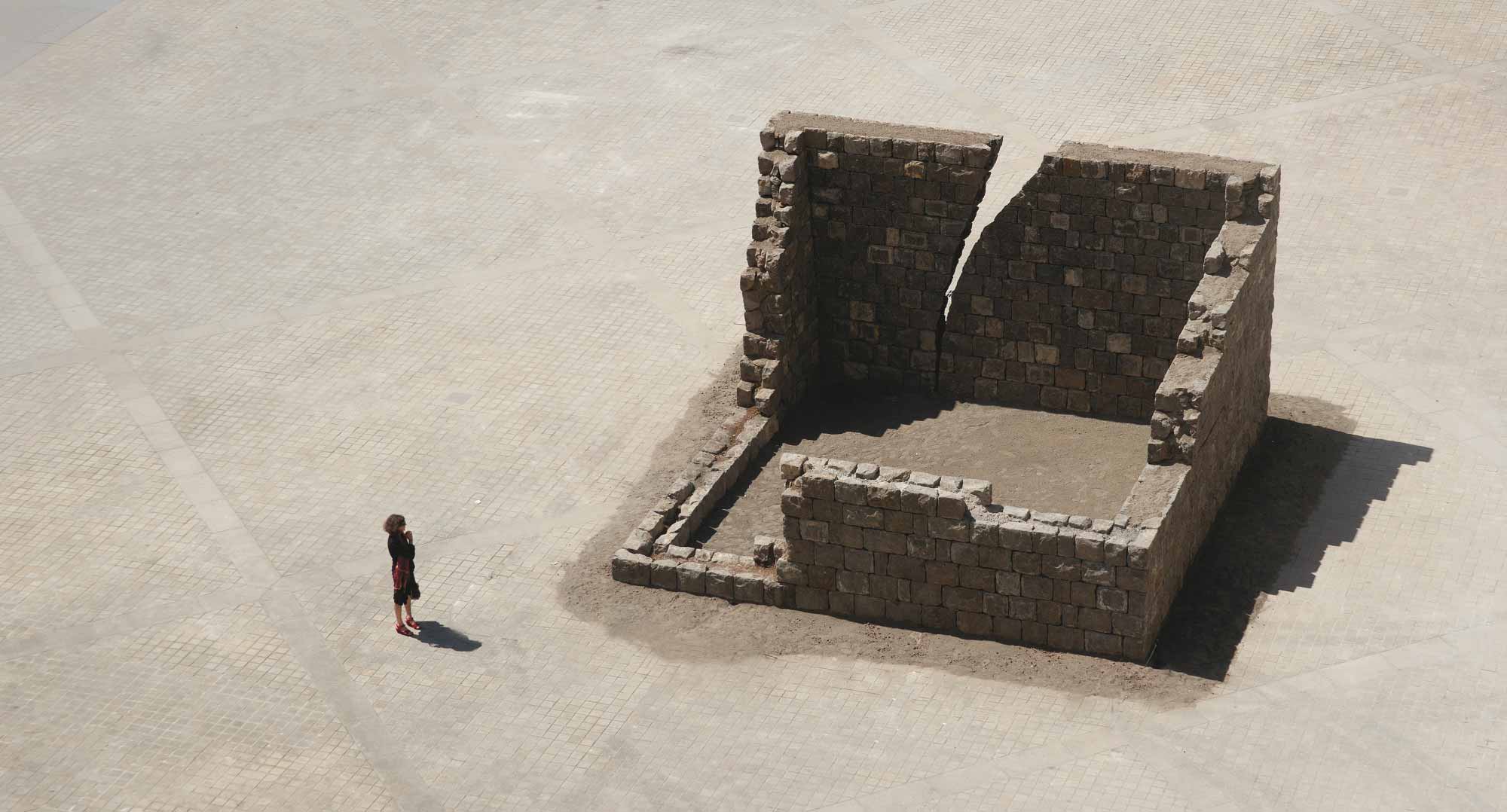

Michal Rovner is a sophisticated artist living in New York and in a small village on the road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. She produces immersive video environments (fig. 2) and more recently, installations of stones gathered from different locations that evoke a mysterious longing for that which is unachievable.

Rovner’s longing for a lost place, is also representative of a nostalgia for lost collectivity. In many of her video installations, individuals merge in hazy air, sometimes fusing into an undecipherable whole, sometimes breaking apart facing one another. Projected on stones, they look like hieroglyphs, archeological inscriptions, or fossils. There is a sense of an open whole that emerges in her work: the flock of birds coming in and out of formation, the gathering of people that become an abstract shape and disappear in the desert heat. An open whole is, of course, a paradox, and a paradox cannot achieve pictorial representation (you cannot imagine an open whole); hence the longing is for something impossible.

Makom IV (Place IV), (fig. 3) recently reassembled in the Cour Napoéon at the Louvre, is indicative and powerful. Rovner collected stones from different places in Israel-Palestine, old Arab villages, as well as early Jewish settlements. Each stone originally belonged to a different home, and has been collected and reassembled for the purpose of this work. The rules for this new collectivity are that the stones will not be carved again, and that the new structure will be produced without cement. The artist numbered the stones so that they can be re-assembled without adding anything to hold them together.

The work inspires a sense of open collectivity as the scattered stones create a home that is the accumulation of many other lost and shattered homes.

Yael Bartana

Yael Bartana’s Wild Seeds (2005) (fig. 4) adds an explicit political dimension to the issue of defunct collectivity. The video installation consists of two projections on two walls and viewers are invited to sit in between both. On one side young adolescents are depicted on a barren West Bank mountain practicing resistance to the evacuation of the Gil’ad settlement. Together they are playing a game that consists of holding on to each other in a tight knot, and in the process learning how to resist planned evacuation. Right wing activists developed this game in response to repeated calls for the evacuation of illegal settlements. The actors take turns playing the authorities trying to break up the young settlers. The close-up on their bodies, as well as the mixture of playfulness and aggression, suggest the sexualized metaphors of conquering a land. A female reform cantor sings the pleasure of the love of god accompanies the scene. On the other screen, single words and short phrases from the game are projected in delayed synchrony. These include: Traitor, I’ll break your balls, A Jew does not deport another Jew, and This is our land.

In another video, Kings of the Hill (2003), (fig. 5) Bartana moves from the hills of the West Bank to the dunes of a Tel Aviv beach. On a Friday afternoon, just before the coming Sabbath, adrenalin-infused young men are pounding the dunes with SUV’s. Of course, this is about Israel, but does it really matter? SUV’s everywhere answer to a primal fantasy of protection and aggression. The background sunset serves as a foil for this new form of romance made ritual.

This work is both funny and sad. It is widely known that Israel is a very macho society — with women granted equal status within the dominating power matrix so long as they serve to advance it. When the country was being formed it needed strong, healthy bodies, with aggression and vitality for the fighting forces. The new Sabra Jew, the reversal of the old Jew of the diaspora — was required to forget weakness as well as compassion and romantic intimacy. Bartana presents a defiant feminist look at this heroism gone astray. Her depiction is critical, but it is also understanding and compassionate. What are those men doing in an entertainment version of a tank, on a Friday evening on the beach, next to the prostitutes (the beach is known for its nighttime activity as well) showing off to their kids? In her most recent Polish Trilogy — … and Europe Will Be Stunned (2007 – 2011) — Bartana experiments with displacement not only of populations, but also of rituals and narratives. In the first video of the trilogy Mary Kozsmary (Dreams and Nightmares, 2007), the leftist activist (and well-known journalist) Slawomir Sierakowski walks into an empty stadium to deliver a heartfelt call to the lost three million Jews of Poland, to return to their homeland: ” … we miss you, our country is not the same without you, please return.” This could have been a convincing argument, if it did not echo Philip Roth’s diasporic alter ego in Operation Shylock: A Confession and delivered in a stadium that references Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935).

As truth follows fiction, Bartana represented Poland in the 2011 Venice Biennale. The trilogy was exhibited under the heading of the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland — JRMiP — a fictional political entity founded by Bartana, complete with a manifesto and a logo. In Venice the audience rushed to sign up for membership. The gesture was seen as ironic and clever, with its strong insinuation to the history of Europe and suggestion of the dynamics that haunt the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In Israel, however, the latest installment was received with less enthusiasm, and seen as catering to a European sensibility or simply forgetting our side. Bartana’s Polish Trilogy manages to irritate even those who take themselves to be post-Zionist. It is disturbing to the local Israeli audience.

Her clean aesthetics, funded by European money, and her growing allusions to uncanny resemblance between Zionism and fascism are now seen less as clever elusions and more like real obsessions. It is indeed telling that internationally successful Israeli artists are suspected of losing the unique and complex perspective that everyday life in Israel sustains. Of course, part of it is plain peripheral jealousy, though capturing the local nuances is indeed very hard. Israel is still a contested and conflicted narrative both internally and globally. The plots are still hotly debated and every shift receives a lot of attention.

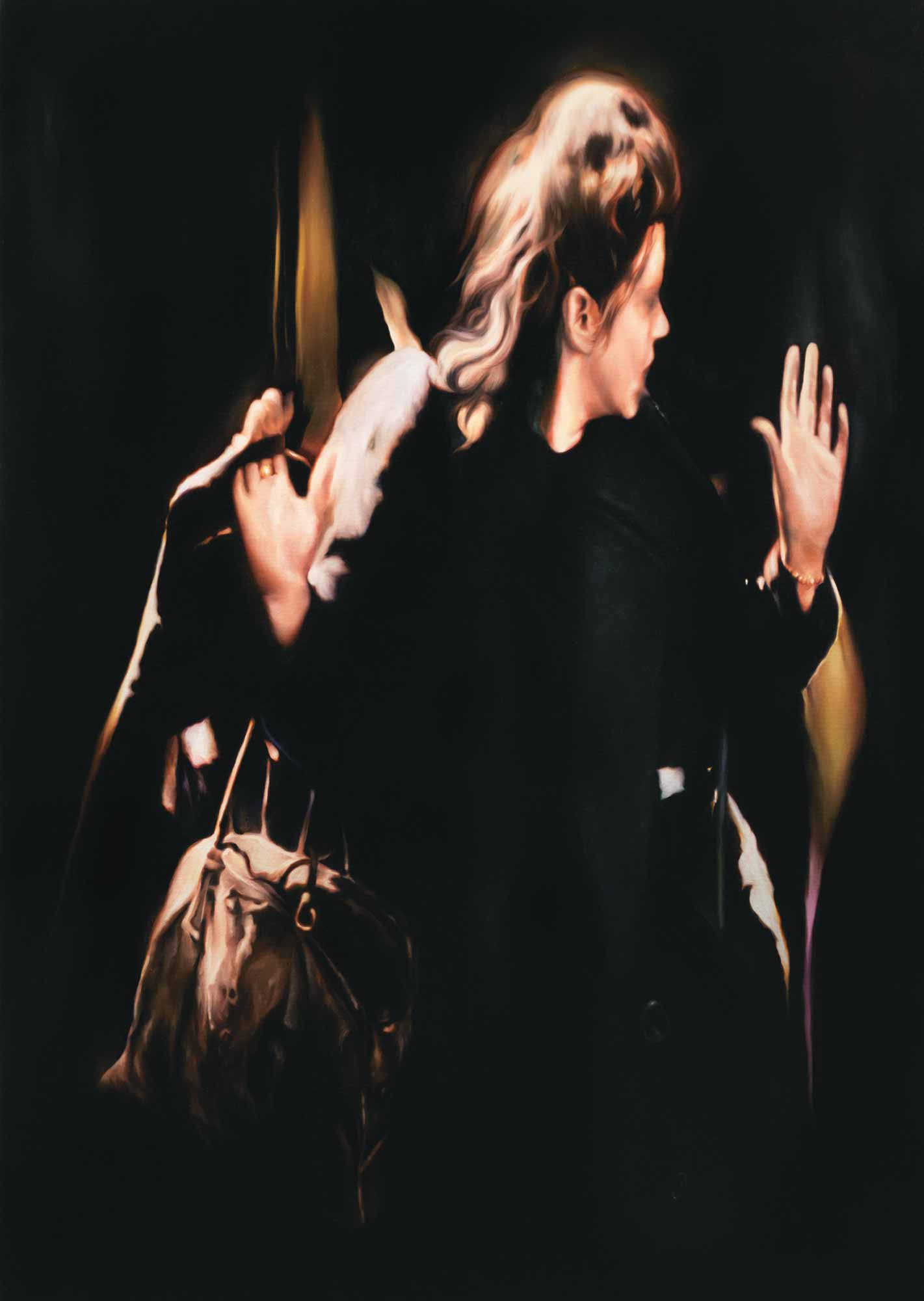

Bartana shares a fascination with fascism with other Israeli artists as different and wide ranging as Nir Hod and the collective Public Movement (founded by Omer Krieger and Dana Yahalumi). Nir Hod approaches fascist aesthetics by mimicking some of its kitsch allure from images of female soldiers to iconic holocaust photographs (fig. 8). Public Movement flirts with fascism by re-enacting the rituals of state-sponsored ceremonies or youth movement choreographies (fig. 7). Bartana’s trilogy, likewise, triggers unconscious hostility as it reveals the buried sources of the Zionist mentality and its core aesthetic values.

Guy Ben-Ner

One of the greatest things about contemporary Israeli art is that it has a sense of humor. There is so much seriousness in the art world and not a lot of self-deprecating fun. It is difficult to be funny in art. Guy Ben-Ner is one of the few hilarious artists. His work, mostly video, is about his nomadic family traveling between Israel, New York, and Berlin recreating their home away from home in various Ikea stores. Here again the sense of longing for a lost home comes infused with the feelings of a pioneering beginning and hopefulness.

In Stealing Beauty (2008), (fig. 9) his family, the main characters in most of his work, are installed in the Ikea model rooms of the different stores all over the world. They act out soap opera-like scenes until the guards throw them out. In the first scene we see Ben-Ner duck behind a shower curtain and begin to bathe. His wife peers into the shower and catches him masturbating. He throws a robe and dashes out, denying her accusation. His son and daughter enter as Ben-Ner pours a drink (we hear liquid, but nothing comes out of the pitcher). Ben-Ner’s wife tells him that his children have been misbehaving. He lectures the kids, mixing patriarchic Marxist and capitalist slogans. Amidst dangling Ikea price tags, he explains that the family unit enables the retention of the value of objects, commodities, and means of production, and that ownership means that one has the right to exclude others. The son then asks: “Is mom private property?” and the kids write a manifesto that includes the statement: “Children of the world, unite.”

Ben-Ner, who represented Israel at the 2005 Venice Biennale, uses a common trope of Israeli art — a kind of do-it-yourself aesthetics utilizing low-tech methods and high ideals. It is simultaneously an expression of the lack of resources and the ethos of emancipation and self-creation that motivated the high-blown ideology of Marxist turned capitalist Zionism.

The Ben-Ner’s behave like misplaced nomads within a globalized and homogenized world. They stand out when they want to blend, and blend in their desire to stand out. It is the journey of one family to find a home in this world and a realization that the only way to be at home in the world is by not being at home in the world.

1 Sigmund Freud and Arnold Zweig, Briefwechsel, ed. Ernst L. Freud, Frankfurt, 1968, p.40.

2 Sigmund Freud, The “Uncanny”, in: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 17: An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works, ed. James Strachey, London, 1953 – 74, p. 217.

3 Sabra is the term for Jews who have been born in Palastine or Israel, as opposed to Jews, living in the diaspora or who immigrated.

4 Robert Smithson, A Provisional Theory of Non-Sites, in: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam, Berkeley, 1996, p. 364.