“Just as none of us is outside or beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings.” (Edward Said) (1)

Geography plays a prominent role in the relations between knowledge and power. The very act of naming a territory and putting it on the map signifies appropriation. Studying the geographical practices used in the field yields a more nuanced view of the connection between the production of knowledge and the colonial enterprise. Scientific geographical practices enabled the practical construction of colonial territory, and the measuring and surveying of previously unknown land in order to transfer it into legible and known space. Maps and surveys form the basis for the translation of topography into a European knowledge system and for controlling and ruling the terrain. Although Italian colonialism was relatively belated in comparison to other European powers, it was nevertheless bound up with broader trends, including a mania for geography in the late 19th century, with the creation of a number of geographical societies such as the Istituto Geografico Militare (IGM) in 1861 and the Società Geografica Italiana (SGI) in 1867, both in Florence. Nation-building was one of the main driving forces behind the growing importance of the discipline. Under fascism, geography’s role at the service of the nation was further strengthened, as reflected in university curricula and the awarding of academic degrees. (2)

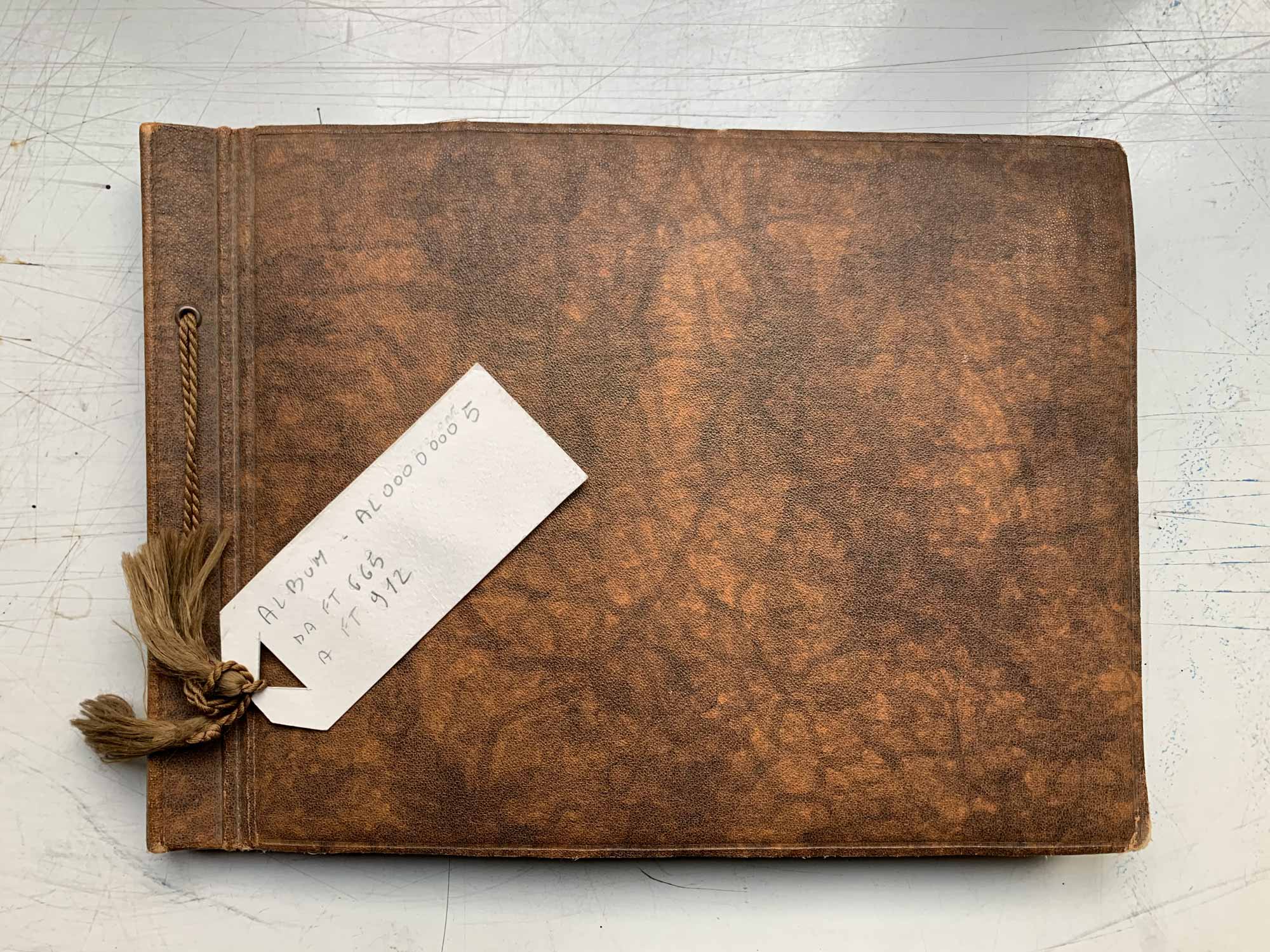

In this context the research undertaken in the framework of the Black Archive Alliance II focused on the Istituto Geografico Militare, Florence (IGM) and its role in the military conquest and colonization of Ethiopia. The investigation explored a rather marginal segment in the archive of Italy’s major national cartography institution, namely six private photo albums, donated to the Institute’s archive by the heirs of two former field geographers. The images in these albums cover a period starting with preparations for the invasion of Ethiopia after Mussolini called for the total conquest of Abyssinia in 1934, through to the establishment of the Italian colonial regime in Ethiopia in 1938/39. In a 1939 publication the IGM itself highlighted the important role it played in planning and conducting espionage prior to the Abyssinian campaign of 1935 – 1936. (3) We can assume the two field geographers explored and documented terrain to find possible routes for the heavy machinery, artillery, trucks and tanks to be used as part of the military strategy to encircle Ethiopia from the north and south, and to survey the hinterland settlements. (4) In 1935 a force of 330,000 soldiers, supported by 87,000 native Askari, left the Italian colonial possessions of Eritrea and Somalia and marched into Ethiopia on 3 October 1935. Just eight months later, after barbarous initiatives on both sides and Italy’s chemical warfare, Italian troops entered the capital Addis Ababa, announcing the fall of Ethiopia on 5 May 1936. (5)

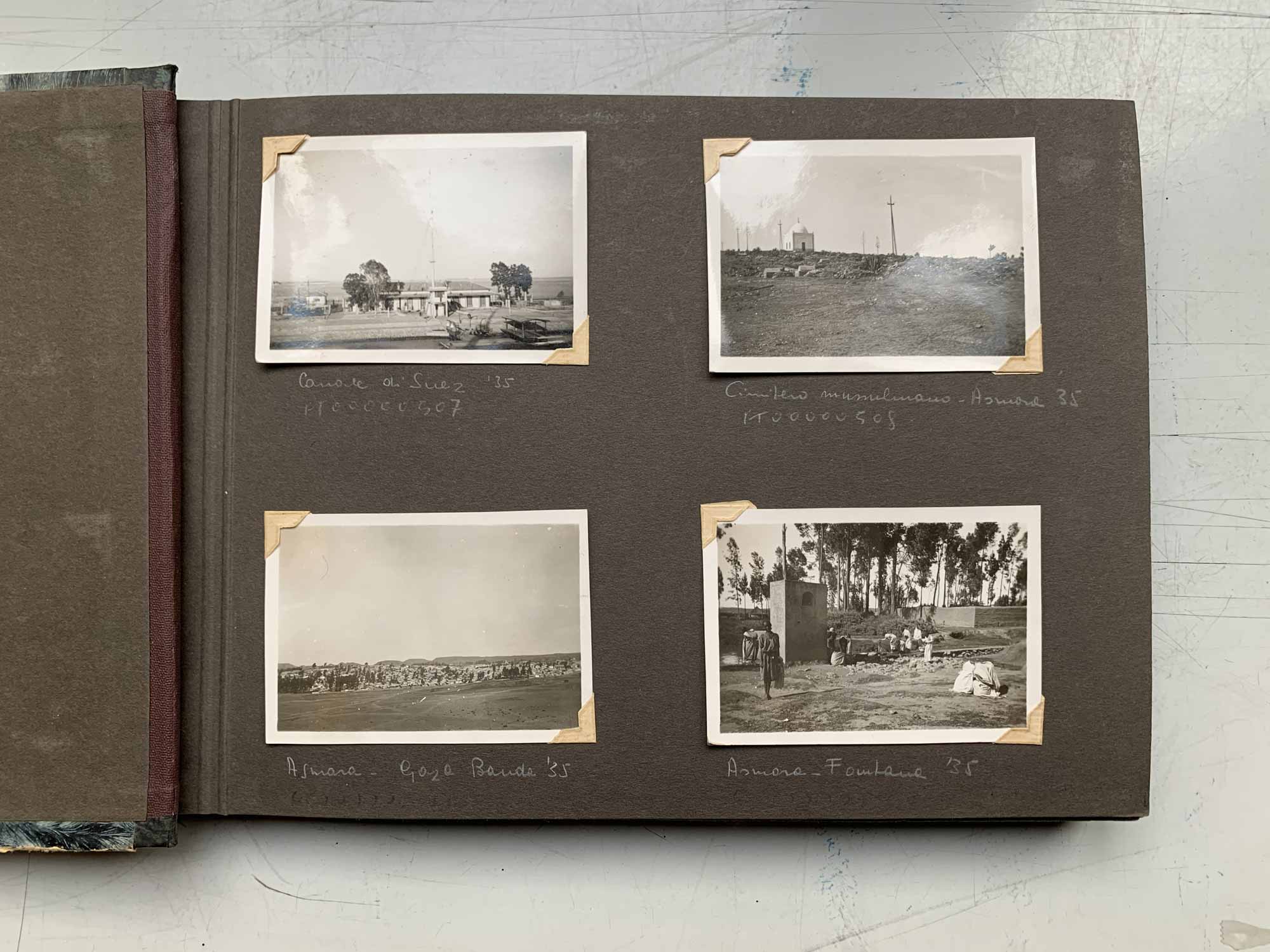

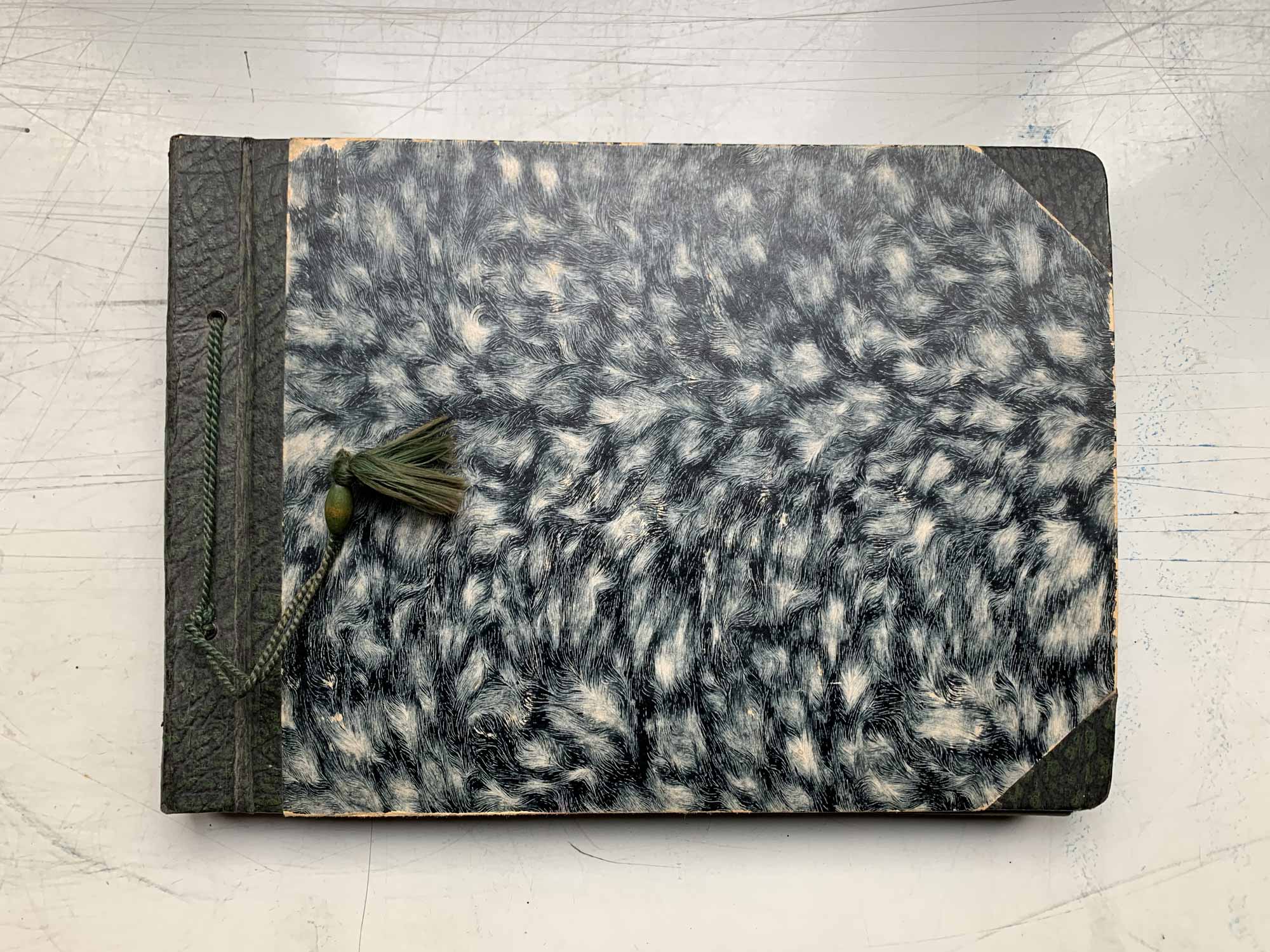

From their outward appearance these photo albums cannot be distinguished from general family or travel albums. They are the same kind of traditional stick-in albums, patterned and decorated, and nothing indicates at first glance that a story of violence will unfold inside. Each picture is accompanied by a handwritten caption with names of places, villages, people and dates. The dates and locations create a linear narrative to reconstruct the routes taken by the photographers. The personal touch in the physical outer appearance also runs through the content: plain professional documentation of the landscapes and settlements, people and objects, that caught the photographer’s attention, alternate with pictures of daily life, comrades and troops. The albums’ narrations open with almost innocent takes of rural landscapes in 1935, with the addition of careful topographical notes of terrain – naming hills, rivers and other landmarks. In these photographs of land – often series of panoramic shots glued together – we seen natural scenery with hardly any huts or settlements. In this void the imagination of the Italian Empire already feels perceptible. The vast empty land seems to offer space for utopias – utopias of expansion, greatness and modernity. The story that would unfold from these images over the following years is the story of how landscape becomes a witness to the violent inscription of power relations. In the subsequent course of the military invasion, we first see temporary interventions, such as military camps, mobile rocket ramps and installations in the open field of exhibited war trophies. For the years 1937 and 1938 it is noticeable in the photographs that the success of the Italian operation was also reflected in the construction of permanent buildings, including churches, monuments and infrastructure. That we are dealing with the album of a geographer is particularly clear when it comes to the documentation of the landmarks of the occupying forces, such as the milestones along the newly built roads – one of the many signs of fascist rule borrowed from Roman antiquity.

There are many facets in these collections of images that prompt observations about science at the service of politics. The photographs also show overlaps with the practice of human geography, in the form of analyses of social structures, demographic conditions and settlement patterns. These reflect the broader political goals of identifying, isolating and classifying the races of the region in the context of a European racial science. (6) With the end of the military operation the fieldwork of geographers eventually led to a popular use and helped to legitimize expansion in the public mind in Italy. For example, Touring Club Italiano, a patriotic organization that celebrated Italian landscapes, extended the horizons of its 490,000 members in 1937 to the new Italy abroad, by publishing maps, magazines and extensive guide books.