A question lies behind the choice of title used here—a question that hung over me as I kept trying to write, and then wrote and re-wrote, this text.

Actually it is a question that I find difficult to even articulate. The question is ironically the one that may be most expected at this moment—the one that, at this point in time, critics, curators and editors will ask artists who come from Egypt. The question has, of course, to do with how an artist, operating at a historical moment, deals with an event whose proportions and form defy all expectations. The question is usually followed by enquiries about whether your practice has changed following such events, if you feel that you have a new responsibility as an artist, if your understanding of art has changed.

Well, the answer to that in my case is quite simply “no.” However, the fact that the question rears its head so insistently in this context is a compelling argument for some kind of explanation of why that is so.

Last year the artist Wael Shawky and I finally, after several years of toying with the idea, and after our highly politicized experience of serving on the jury of the 20th Youth Salon in Cairo, 2 decided to take active steps towards realizing an exhibition together. The significance of this decision immediately became clear to us as we talked about our ideas; the conversa- tion was very smooth. We described a series of works to each other that we imagined would be shown collectively in a twenty-meter-long vitrine. The works, very different in tone and tenor, shared something that Wael and I had found to be important. In a sense it felt as if we were, in our own ways, shoveling hard, crystallized fully formed pieces out of our memories. These pieces were not memories, though; they were transformations.

They were pieces that were not figments of the imagination, but rather actual things from a collective landscape that we from our respective back- grounds were part of, belonged to and drank from.

The first lesson I remember learning, which may not be the first lesson I actually learnt, is that humiliation exists. This is something that I deeply absorbed as a child. My mother, in a way I suspect she was not fully conscious of, constantly pointed out to me this condition in the world. Last year, through working on that show that in the end did not take place, I realized in a personally involved way that I had learnt this lesson in a profound and deeply felt fashion many years before. This was the first time that something that has always been clear was finally stated, whispered back as a secret thought.

To put it simply, that collective landscape (deeply influenced if not completely shaped by the lesson learnt all these years ago) has been the source of my work. It is also where the answers to the questions about how an artist should respond to the revolution that are being, and will continue to be raised by the art community, both locally and internationally, lie.

I thus thought it best to present here one of these sublimations, one of these charged aesthetic facts, as an answer that one finds less problematic and ultimately more useful than any explanation. For I believe explanations are now not necessary unless they serve the revolution in a direct and practical fashion; anything else is fetish and representation and counter-revolution.

The short story that follows this introduction has developed out of one of those transformations.

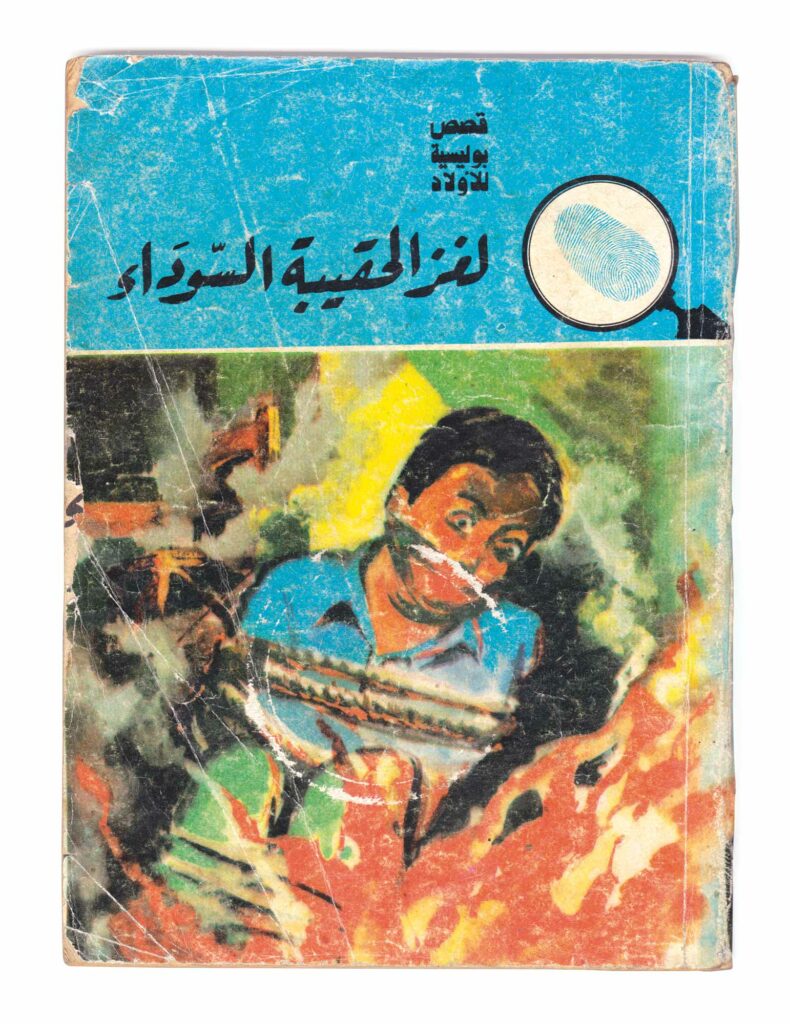

I wrote a fragment of this text in mid-PQRQ, in a stylized accented Arabic that referred to the popular literary style of cheap paperback novels. The piece was based on my memory of reading and collecting as a child a series of pulp novellas for young boys. These novellas were roughly based on Enid Blyton’s renowned Famous Five series. In Arabic the subtitle of the book was Police Adventures for Boys. I remember hungrily reading these novellas, though I do not remember any of the details of the many adventures that

I consumed. Funnily enough, the one description that keeps returning to me regularly over the years is one that reappears in many of the different novellas; it describes the five young friends, usually in a car speeding through the night. Maybe it’s a police car and they are in it to catch a thief whose identity they have managed to uncover. The car was described (and here I am translating quite roughly) as “penetrating the quiet suburbs of Maadi.” For some reason those words have remained with me through the years. They must therefore mean something but I am not sure what that

is exactly. To this day those words sometimes ring out in my head when, late at night, I am in a car that is smoothly speeding through the empty streets of Zamalek, or some leafy, quiet street in Maadi. I remember this phrase as if this city has lived its days under a sign that I did not know. Whenever it returns to me I have a distinct feeling that I am cutting through the streets of another city unknown to me, but that is still mine.

The idea for the exhibition piece was to write a fragment from a novel and to print it on three pages torn out of one of The Five Adventurers novellas I used to collect, in exactly the same font and layout. I have already produced fourteen pages in Arabic; the piece is called Mystery. For the purposes of the text here I have written a slightly different version in English.

Mystery: A Short Story Based upon a Distant Memory with a Long, Imagined Musical Interlude

Dr. Mahmoud looked down at the cheap notebook that he had just found in one of the drawers of the second-hand desk he had bought recently. He opened the notebook slowly and let the pages fall open randomly. And as he, still standing up, began to read the first page his eyes fell upon, he noticed that the handwriting was very neat and careful. It seemed that there was a level of deliberation behind the words. This is what Dr. Mahmoud read first.

Thursday / Midnight / Diary entry no. 26

It’s a really hot night and I don’t want to switch on the air conditioning, I am therefore sweating heavily and I kind of like it like this. I feel like someone with an insistent fever who as much as they want it to disappear will miss it when it’s gone deeply and with great longing. It might have something to do with the strange moment I experienced today while driving back home from my first meeting with Dr. Seddiq. It was a difficult and heavy moment. But it was also, unexpectedly tender at the same time. I was driving my car, it was midday and the streets felt strangely empty, when I was suddenly overwhelmed by the desire to stop the car and rest for a moment. Like that, in the middle of the street, suddenly and without any hesitation, to stop for a second. I felt slightly unbalanced. I had to stop the car but didn’t know exactly why, so I just did it, suddenly, in the middle of the road. But I was immediately interrupted by the loud aggressive honking of the microbus behind me. I felt an electric surge of anger. I wanted to step out, walk back, open the door, grab the driver by the head and snap his neck, but then immediately I was gripped by a deep and ancient exhaustion. So I started the car and drove home.

Dr. Mahmoud who had by now seated himself comfortably in his soft, expensive easy chair, raised his eyes from the pages of the notebook, closed it and turned the diary round, noticing on the top right corner the name “Mohsen El Bana” elegantly, almost pretentiously, printed. He looked deeply into his wife Nevine’s face—she seemed oblivious to his intense gaze as she flipped through a property brochure—he returned to the pages in front of him and continued reading.

Sunday / 2am / Diary entry no. 34

The night is quiet and I have switched off all the lights in the flat. However, the air conditioning is on and it’s quite com- fortable. It has been an exhausting evening. I went to dinner at a new, trendy Thai place with Tarek Selim, Yehia El Nady and his girlfriend Heba El Wakil. I realized that I hadn’t seen these guys for at least a couple of years, since we all hung out that summer when Basil Mortada came back from the US, before leaving again in September. I feel content but a bit worried. Something is wrong. I don’t know what exactly. Throughout the evening I couldn’t really focus on the chit- chat, being constantly distracted by the image of Dr. Seddiq’s smug half-smile. That mothefucker always employed it with such deadly precision. Whenever I referred to a new work strategy, or even when making a joke about the color of the new car I had just bought, whenever I started speaking in English. Dr. Seddiq’s shrug and smile always managed to throw me off balance. I can’t understand how that ignorant bastard manages to pull this off every single time. Today as we sat in his office I began sweating heavily—me sweating like a nervous novice. I looked at Lamia at that moment, but she carefully looked the other way. I could tell she wanted to laugh at me. Well, Dr. Seddiq’s empire of private schools, fake academies and bus transport companies cannot hide the fact that he is an ignorant overdressed oaf. It definitely didn’t stop him from dismissing my requests for a higher salary in front of everyone! Everything I had gained disappeared in his simple arrogant gestures. This man only feigned respect for others for his own reasons. Doesn’t he realize who he’s dealing with, the quality of the person sitting in front of him? We were suddenly two uneasy monsters looking at each other across the room. He was a monster who could draw upon enormous resources and didn’t care what others thought, I was a monster begging for recognition, for the person in front of me to admit that I was not of his ilk. And all he had to do was look at me as if we were friends but not exactly— a slight smug smile told me that he knew exactly what I could really afford and what I couldn’t. He had called my bluff.

Dr. Mahmoud raised his eyes from the pages of the diary of Mohsen El Bana and looked again, deeply, into his wife Nevine’s face. She remained oblivious and was now casually checking her Facebook page. Dr. Mahmoud felt unsettled but he couldn’t place his finger on the reason why exactly. It seemed that these direct simple sentences had affected him deeply. He felt slightly and in a subtle fashion sad but couldn’t really tell why.

The sounds of the hysterical beats and the plastic seesaw synth of the music that had taken over the streets of the city wafted in through the open window, and he looked up with consternation. He had wanted to abandon the city this summer—to place a distance between himself and this place, this angry, dirty, crowded mishmash of buildings and intentions. For here the days passed without understanding the meaning of the days—except maybe, and here he thought to himself with a slight twinkle, very slightly. Suddenly and without warning he remembered the mysterious novellas of his childhood.

As a child Dr. Mahmoud read a lot of police adventures for boys, in the mid-range eighties apartment, on the faux leather couch, in the heat of the summer hungrily reading page after page, following how Takh Takh, Nousa and their friends always solved the case. Each time he found a strange excitement in the description of a car that carried the five young sleuths cutting through the calm suburbs of Maadi. The suburbs. It was strange, he thought to himself, how not a single detail remained from those tales of mystery and innocent crimes cracked by a group of seemingly free-spirited boys and girls in shorts, moving through a strangely empty, calm, harmonious city that he didn’t know. Even then, even in his childhood. His mother, then young and to his eyes absolutely radical, a psychological force of nature, was studying for her high-school diploma with the daughter of the bawwab, the door-keeper of the vaguely upper-middle class yet mid-range apartment building. She had taught him to recognize humiliation in the world around him—to see how it worked, how people used it and what it made of them. And maybe more importantly what it made of him. Dr. Mahmoud suddenly remembered the book club that, maybe in an unconscious attempt to emulate his seemingly class-free mother, he had begun with Nasser, the son of the bawwab, who lived in a tight smelly room with his mother and sister. Nasser’s father, the bawwab, was mostly absent, caught up in the drama of, it was whispered, abandonment and second marriage. The young Dr. Mahmoud, who had collected a large amount of the novellas and stored them in a big black plastic bag, would regularly carry them down the six storeys to sit with Nasser and exchange some of his for those that Nasser had collected. They discussed the latest exploits of the five adventurers they read about. As far as he remembered there was nothing especially interesting or exciting in those encounters. They were not exotic or out of the ordinary in any way—if anything, these encounters with Nasser the bawwab’s son were probably colored by some sort of dumb, childish functionalism more than anything else. He also remembered the extreme reactions he faced when he told his friends at the English-language school in the quiet suburb of the busy city about his book club, about the daily comings and goings between the fifth floor and the room in the basement. His classmates’ look of bewilderment and surprise surprised him—but not entirely. Things were much clearer now that he in a sense understood how things actually operated.

Dr. Mahmoud suddenly realized that he had been daydreaming while staring blankly at the pages of the notebook. He continued reading.

Tuesday / 1am / Diary entry no. 43

It’s a relatively cool evening with a nice breeze, the balconies are open and there are kids playing football in the street. Today I had another upsetting meeting with Dr. Seddiq at his office. He had me sitting there in front of him for half an hour to tell me about how things should be done in his system. He was careful not to tell me that I worked for him, but he never failed to point out that this was his business. As he droned on and on I realized that actually I admired this corrupt, ignorant man, for to him at least things were clear. He knew in a way that involved no shame, in a way that broke everything that came in front of him, that this was all in the end an elaborate pretence. That we were caught in a banal game of alignments and that the words he used, the tone they were said in, the smile that came to him naturally as he told a joke or the frown on his soft face when he barked for his driver and car, the courteous way he received people he needed things from, the casual way he despised the world as he relished it, were all ultimately things that did not in any way affect how he saw himself. I suddenly felt at that moment that I wanted to shout out loud without embarrassment or hesitation. I saw myself sitting in the over-decorated chair, in my tasteful shoes and with my trimmed goatee, with my opinions that I wore like an expensive jacket. I saw myself and I wanted to push myself out. I wanted to stop the people walking in the streets, to stand in front of them as they insulted each other in the most poignantly poisonous fashion. For I was also one of those who said “Ya Waty” who shouted “Yalla.” I drank their water and ate their food. I can’t remember what I was thinking when I stepped out of this office, though. What was I thinking when I got into my car and drove back to Maadi? What was I thinking then? Why am I writing this now?

Dr. Mahmoud suddenly stopped reading to find that he was completely alone in his living room. Nevine had gone to bed and he was confused.

1 This essay is a reprint of the text that originally appeared in 2011 in Index, no. 2 the magazine of the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA). An earlier and slightly different version of this text premiered as a live lecture-performance under the title A Short Story Based on a Distant Memory with a Long Musical Interlude at Objectif Exhibitions in Antwerp on May 6, 2011. The short story included here also exists in Arabic as an art piece called Mystery (2011) that was first shown at the Beirut Art Center in the group show entitled Image in the Aftermath, which opened on May 17, 2011.

2 For further information and in-depth coverage of the events in Cairo, Eygpt please visit the websites of e-flux journal and Universes in Universe.